| arts & style > art | more art stories >> |

|

|

|

||||

EDITIONS |

|

|

Paul Oxborough's modern paintings have Old Master's grace

NEW YORK (CNN) -- The self-portrait of the young artist, done in rich dark tones, looks like a work by Rembrandt. The vibrant painting of an elegant woman in a soft yellow sweater looks like a society portrait by John Singer Sargent. But both paintings are by Paul Oxborough, a young artist from Minnesota, whose work at the turn into this new century recalls the master painters at the turn of the last. In an age of video installations and conceptual art made with anything from neon to embalmed animal parts, Oxborough, 35, works with the materials Renoir used: a muted palette of oil paints; a canvas of fine Belgian linen.

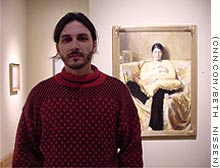

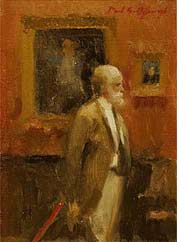

At first glance, many of the figures in his work look Old World. The white-haired man in "At the Museum" has the face of a Victorian gentleman -- but he's dressed in a contemporary jacket and tie. The refined woman in the yellow sweater is seated on antique gold brocade -- but posed loose- limbed in black slacks. "Almost all my work comes from real life," says Oxborough, a slender man with a long, dark ponytail and a beard that is not altogether successful in making his face less boyish. "I paint things I actually see: my wife Jenny on a train, my daughter waking up, a guy in a museum." "And I paint the way I think people see -- not with photographic accuracy, but with impressions. I think of myself as an impressionist -- painting the impression of light hitting your eyes; the impression of color you see at a glance." The Crayola periodOxborough has loved making art for as long as he can remember.

In his earliest years, his Crayola period, "I was just another kid, drawing on the walls," he says with a laugh. But by grade school, he was already showing promise in drawing. "I remember being in fourth or fifth grade, and there was a minishow where they put our work up on the walls -- and I remember mine was the best. That isn't to be prideful. I just could see that mine was the best." By the time Oxborough entered St. Louis Park High School in suburban Minneapolis, he was "serious about my art," and lucky enough to have an art teacher, Robert "Doc" Anderson, who both recognized and encouraged Oxborough's talent. "He was my first mentor," Oxborough says. "He loves, really loves, painting. He taught me so much. He told me that you had to look at an artist's life, not just their work." The prevailing stereotype of the "artist's life" had troubled the young Oxborough. "You think when you're starting out that being an artist means wearing lots of ripped-up clothes, living a funky life with paint all over the place -- the Bohemian life," he says. "I remember being 18 and having a conflict about that. I didn't have a lot of angst. I respected my father; people who worked and wanted their kids to go to college; people who'd been married for 40 years. I wanted that for myself. "Doc Anderson said, 'Well, look at Monet -- he had four stepchildren and three children. He was a nice man; he paid his bills on time; he did all the things that Mr. Cleaver did -- and was still a great painter.' And I loved that. I thought, I can do this." French influenceAfter high school graduation, Oxborough attended the Minneapolis College of Art and Design for a year, then went through four years of rigorous study in a local atelier, or artist's workshop, studying art in the French academic tradition.

"That's another connection to Sargent," Oxborough says. "That's the way he studied -- working from nature, working from the model." And working, for the entire first year, on doing drawings only, in black and white only -- no color, no painting. In the second year, he advanced to working with oil paint -- but only in black and white. It was elemental, fundamental training that Oxborough believes is essential to a fine artist, akin to a musician mastering scales and intervals before becoming a virtuoso. "White's the hardest to paint, I think," says Oxborough. "You paint something white, there's no really true white on the canvas -- pure white out of the tube. I use all of my colors to mix an impression of white." One of Oxborough's most admired paintings is "First One Up," an early-morning scene of his wife and two daughters stirring awake in a London hotel room. Sunlight streams across a rumpled expanse of bleached bed sheets that seem painted with broad brushings of pure white. But the "white" sheets are rendered. surprisingly, in lavender, blue, pink, yellow and aqua. Painting, travelingOxborough spent the better part of a year in Europe after completing his atelier training. He and his wife took their four children to France for several months; the family later traveled to Spain and Portugal, England and Wales.

Much of Oxborough's work makes up a kind of family album -- of color "snapshots" done in oil: his son in a Portuguese barnyard; his daughters crossing a river in a French ravine; his daughters and his wife in a London hotel room. Oxborough's wife, Jenny, is his favorite model and muse: He has painted Jenny at the piano, Jenny on the patio, Jenny at the family dinner table. "I've painted her hundreds of times," says the artist. "Part of it is, she's always willing to sit for me," he says with a laugh. "She especially loves napping poses." Oxborough is a thoughtful, deliberate painter. He prefers to paint scenes that are still, to paint figures posed in repose. "I like the idea of people working, moving, but that's hard to do -- it's hard to capture people in motion," he says. "I have a lot of people at rest, for obvious reasons: because they sit still." Yet the two men shown standing motionless behind the bar in "The Bartenders" are not static; they're just in a lull between an order for a martini straight up and another-sad-story cried into a beer. "It's the end of the night and they're done," says Oxborough. "They're not moving, but we know that they were, and will again." Captured momentsMany of Oxborough's works are captured moments like this. He tries hard to vary his scenes; not to do too many paintings of bartenders, of Jenny sitting at a table. "That can be a dangerous trap," he says "You can be typecast -- 'Oh, he's the guy who does the women on the beach in white dresses.'" He shouldn't worry. The New York City gallery that has handled Oxborough's work for four years cites his broad range for the growing demand -- and price collected -- for his paintings. "There is such diversity to his subject matter, and palette -- from dark interior scenes to dappled sunlit exteriors," says James Umphlett, vice president of the Eleanor Ettinger Gallery. Oxborough has the skill to capture the exact quality of light from any source: the warm flicker of a candle through milk glass; the harsh buzz of a fluorescent tube under a mahogany bar; a shimmer of July sunlight over a meadow; an icicle of light through a northern window in Minnesota in February. He will spend hours painting and repainting light -- the way it glints off a gold wedding ring, the way it forms shadows in the folds of a dress, the way it falls from under a paper lampshade. "It's hard to make a hunk of paint look like a light that's on," he says. A perfectionist's eyeBut he can, and he does. Those who collect Oxborough's work almost invariably mention his rendering of light. "His painting uses light in an incredibly skillful way," says New York City art collector Joan Rosenberg. She and her husband Neal have four Oxborough paintings in their collection, which includes Jasper Johns, Lichtenstein and Picasso. "That's exactly what draws me to his work -- that kind of talent." Oxborough has nine new paintings in a current exhibition, "The Figure in American Art," at the Eleanor Ettinger Gallery. They range from a sun-splashed portrait of Jenny to a candlelit study of a man in thought. They range in size from "The Bartenders," a wall- filling 4-by-3 feet, to "At the Museum," just 7-by-5 inches. In New York for the opening of the exhibition, which runs through February 11, Oxborough cast a critical eye on his nine paintings. He admits he is a perfectionist -- perpetually unsatisfied, even after 100 hours of painting and repainting a single canvas. "I see my works, and it's all a bunch of mistakes to me," he says, with a rueful shake of his head. He points to "The Bartenders." "There's 20 layers of changes under there." "Some artist said, 'You never like a painting; you just give up on it.'" Paint atop paintHe says his studio in Minneapolis is full of paint-stratified canvasses he's given up on -- at least for now. He throws out those that are so paint-laden they cannot hold another daub. "For every painting I do, there's another painting that I think I can paint and I end up not being able to. I haven't unlocked the mystery of it," says Oxborough. He indicates the smallest painting in the exhibit, the little 7-by-5 inch portrait of the elderly man in the museum. "I saw this man at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and I made a quick sketch of him. I planned this as a much larger painting, but when I tried to make it bigger, it didn't work. It lost all of its charm. Maybe I didn't have enough detail of the man -- and I can't go back to Oxford to find him." But a careful look at the little painting shows a wealth of detail about the man, detail painted and implied: the press of his white shirt; the weave of his tweedy jacket. He is not just a man, but a gentleman; not just older, but an elder. Subjects with storiesLike so many of Oxborough's paintings, what is visible in the frame suggests what is not visible outside it: The gilt-framed portraits in soft focus in the background suggest what the elder gentleman is looking at. He is looking at fine portraits -- and has become a fine portrait himself. Oxborough says he often makes up stories about the figures he paints -- their histories, their relationships with other figures in the painting. He says it helps him paint their expressions, the way they hold themselves, if he supposes aspects or and reasons for their characters. I wonder about the elder gentleman in the painting. Maybe he is lonely, and has gone to the museum to be in the company of others who share his appreciation for beauty. Maybe, in his winter years, he needs a museum's reminder that humans can produce something ageless and lasting. This is Oxborough's especial gift: To observe such a moment. To preserve such a moment. Within minutes, I form an attachment to this gentleman -- this arrangement of paint on linen and panel. It will take me a year to pay off my credit card for the privilege, but I buy "At the Museum." I will put the little painting in my study -- this image of a man in the presence of art; this image of a man exemplifying art at its finest. RELATED STORIES: Impressionist and modern art sale raises $140 million RELATED SITE: Eleanor Ettinger Gallery |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

N. Y. plans to heal skyline

Stocks rise on Case departure

Lieberman's presidential announcement today

New arrests may be linked to UK ricin scare

MARKETS |

4:30pm ET, 4/16 | ||

144.70 | 8257.60 | ||

3.71 | 1394.72 | ||

10.90 | 879.91 | ||

Jordan says farewell for the third time

Shaq could miss playoff game for child's birth

Ex-USOC official says athletes bent drug rules