Edward Winter

‘The stalemate is the penalty for mauling without killing’ was the prize-winning entry in a New Statesman competition in the 1950s. The remark came from a Mr Hamburger, according to Assiac, the Statesman’s columnist (see page 63 of his book The Pleasures of Chess).

In the present compendium of little-known examples of stalemate, we begin with what is probably the most common form, arising in a queen ending:

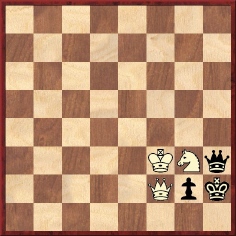

C.A.

Walbrodt – T. von Scheve, Berlin, 1891 (Black to move)

81…Qd6+ 82 Kxd6 Stalemate.

Source: International Chess Magazine, September 1891, pages 269-271.

A similar example comes from an offhand game at the Melbourne Chess Club between unidentified players:

White to move. Play went 1 g7 Qg4 (Black could win with, for example, 1…Qd4+ 2 Kf7 Qd5+ or 2 Kg6 Qg4+.) 2 g8(Q) Qxg8 Stalemate.

Source: BCM, June 1916, page 195.

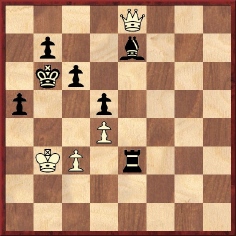

C.

Wieckmann – Labbé, Reval, 1903 (White to move)

Play continued as follows: 1 Nf4+ Kf1 2 Ne2 g3 3 Kf3 g2 4 d5 h3 5 d6 h2 (Black misses 5…g1(Q), which would win.) 6 Ng3+ Kg1 7 d7 h1(Q) 8 d8(Q) Qh3 (‘The only move.’) 9 Qd2 Kh2 10 Qf2

10…Qg4+ 11 Kxg4 Stalemate.

Source: Deutsches Wochenschach, 17 January 1904, page 24.

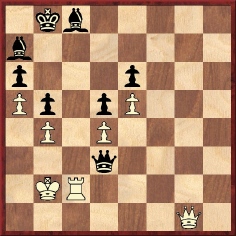

The above position (White to move) occurred in a game at the Perth Chess Club, White being the 15-year-old Vernon Stannard. He played 1 Re8 c2 2 Re1 Rd1 3 Re2 c1(Q) 4 Rc2+ Qxc2 Stalemate. With 4…Qxc2 Black contrived to play the only move which did not win.

Source: Australasian Chess Review, 30 April 1939, page 94.

L.G.

Eggink (simultaneous) – v.d. Wyngaard, Magelang, 1911 (Black to move)

Instead of moving his attacked knight to b1 or b5, Black played 1…Nc4, setting up the mating threat 2…b5. However, White obtained an immediate draw with 2 Rxb7+.

Source: Deutsches Wochenschach, 3 September 1911, page 320.

This position, with White to move, arose in a correspondence game between Kandler and Josef Schwarzbach. Black has just played his rook from e4 to e3, and White replied 1 Ka4. Now it may seem that Black can win by 1…Rxc3 2 Qxe7 Ka6, threatening 3…b5 mate, but White achieves stalemate by means of 2 Qd8+.

Source: Deutsches Wochenschach, 15 January 1911, page 26.

J.H.

Blackburne – S. Winawer, Dresden, 26 July 1892 (Black to move)

Black played 49…Rxd3, which Blackburne answered with 50 Rxf8+, and the game was drawn. If 50…Kxf8 51 Qxh6+, and White will draw by stalemate.

Sources: Deutsche Schachzeitung, September 1892, pages 270-272 and the Dresden, 1892 tournament book, pages 167-169.

L.

Jellinek – G. Heilpern, Vienna, 13 May 1915 (White to move)

Play went 1 Qc1 Bxd4+ 2 Ka2 Bb7 3 Rc8+ Ka7 4 Ra8+ Kxa8 5 Qc8+ Ka7 6 Qa8+ and stalemate follows.

Source: Wiener Schachzeitung, March-April 1916, page 96.

The finish is ingenious but 1…Bxd4+ was by no means forced, as 1…Qxd4+ or 1…Bb7 should win for Black. Moreover, from the diagrammed position, White could force the draw with 1 Rxc8+ Kxc8 2 Qg8+ Kb7 3 Qf7+ Ka8 4 Qe8+ Bb8 5 Qc6+.

Finally, a position in which a master misses a simple stalemate opportunity. It happened in the game between E. Lundin and W.R. Hasenfuss at the Prague, 1931 Olympiad:

Black played 68…Qb8+ and had to resign ten moves later. Instead he could have drawn immediately with 68…Qe6+.

Sources: Šachová Olympiada v Praze 1931, page 227 and Tidskrift för Schack, August-September 1931, page 157.

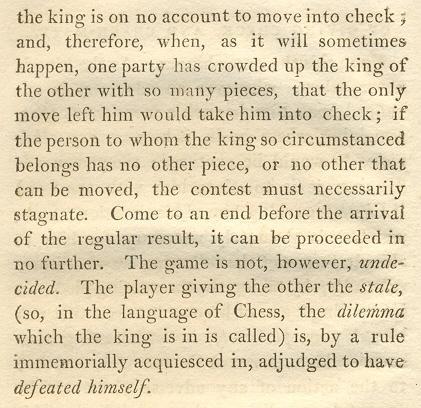

As is well known, it was only in the early nineteenth century that stalemate came to be regarded as a draw. The old rule is shown in the excerpt below from page 32 of Studies of Chess (London 1803):

For an historical tailpiece here, it may also be noted that even in the mid-nineteenth century there was still discussion about whether an en passant capture, normally optional, was obligatory in cases where it relieved an otherwise stalemate position. On page 5 of his 1860 book Chess Praxis Staunton wrote:

‘A “forced move” is when a player can only make one move, and the taking a pawn in passing is to be considered a forced move when the player has no other.’

Charles Tomlinson recalled on pages 501-502 of the November 1891 BCM that the above wording had come about after he had submitted for discussion the following position:

‘I set up the annexed position, and put the question whether, in order to escape a stale mate, the second player could be compelled to take the P en passant. In this position, White having to play, advances the Knight’s Pawn two squares, whereupon Black calls out Stale mate! No, retorts White, you can take the Pawn en passant. But that is at my option, returns Black, it is a purely voluntary move, and I don’t choose to make it. In this contention, I held Black to be in the right, it is a purely voluntary move, and the definition of a stale mate as generally given, to be faulty:- “A stale mate is when a player whose King is not in check, and whose turn it is to play, has no move except such as would put his King in check.” The committee [on revising the laws of chess, comprising Messrs Löwenthal, Ingleby, Wayte and Tomlinson] agreed with me that the law required amendment…’ [This shows that capturing en passant is not always a ‘privilege’, to quote the term used twice on page 93 of An Illustrated Dictionary of Chess by Edward R. Brace.]

Another simple position illustrating the point appeared on page 21 of The Kipping Chess Club Year Book 1943-1944:

Mate in two moves

Solution: 1 c4 dxc3 2 Ra4 mate.

Suggestions for further reading on stalemate:

Further specimens of stalemate are indexed in the Factfinder.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright 2007 Edward Winter. All rights reserved.