|

Home

|

Game of the Century?

Kasparov Analyzes

Garry Kasparov:

“I only fear that after January 20, 1999 it will be very difficult

to persuade people that my best game has not been played yet.”

“My best game has not been played yet…

We have heard

this traditional answer so many times from famous

chess players irrespective of their age and degree

of professional success.

The dream of playing a game that would highlight a chess player’s

entire career – no matter how many brilliant games have been played

or how many original combinations have been revealed –

this dream is like an engine that leads chess players

to reveal new depths of the game.

I only fear that after January 20, 1999 it will be very difficult

to persuade people that my best game has not been played yet.

The concept “best game” is very subjective:

some like combinations or a shrewd positional game;

others choose their own criterion of beauty.

There is no universal definition that would satisfy

everyone. Any chess player has individual

aspirations and preferences that define his

criteria of perfection in chess.

In my career, there have been many games

that would satisfy the most severe connoisseurs of

chess. However, only a few qualify for the title

“the best of the best”. Two of them, by the way,

are among the three that are considered to be the

best for the whole period of publications in the

Chess Informant. First, the 16th game of my 1985

match with Karpov. Second, the 10th game of the

1995 match with Anand. And even these games had

some hidden defects: a pawn sacrifice in the

opening when I played Karpov was objectively

incorrect; and as far as the game with Anand is concerned,

true and severe connoisseurs realize

that preliminary preparation diminishes the overall

beauty of the game, though the main criterion of

beauty is the impression produced by the game or

combination on the audience.

It is very difficult to describe a perfect

combination that can fascinate chess admirers,

especially now, in the end of the 20th century,

when amateurs and grandmasters have computers at their disposal.

Any combination, any sacrifice,

can be analyzed not only by keen chess analysts but by

any person who knows a slight bit about chess,

can afford a powerful computer, and can help it move

around the maze of opportunities.

Therefore, the criterion of beauty today should include

the overall correctness of the idea,

even allowing for certain human defects,

as there is no combination without the partnership of two chess players.

The rightness of a combination, its harmony and

accuracy, are now seen much more quickly.

It no longer takes years or months; the final verdict

will be announced in a few days or weeks.

It is clear that the ultimate combination should have

a thrilling element, such as inevitable mate or sacrifices,

where one’s mind rules over matter.

It could be a combination with a mating attack,

allowing a mating net to be spun with minimal effort.

This is something that everyone likes.

In the long run, the final aim of the game of chess is

to mate the King of the adversary. Unfortunately,

modern defensive technique does not let us fulfill

such combinations, but nips them in the bud.

A piece and even a pawn sacrifice are now regarded as

something special, let alone a Rook sacrifice,

which has already become a relic in the games of

leading chess players, when done without an obvious

combinational motive. Moreover, legendary marches

of the King through the chessboard, when White or

Black monarch has to cross the minefield under a

hail of fire, are buried in obscurity. The time of

“evergreen” and “immortal” games by Adolph Andersen

has also sunk into oblivion. I least of all

imagined that one day I would be able to revitalize

the rebellious and romantic spirit of the

chessboard and to create a combination that would

conform to all of the above-mentioned severe criteria.

I came to the tournament in Wijk aan Zee

with mixed feelings. It was too important for me

after 11 months of forced downtime. Of course,

I had gathered much potential energy.

My preparation for the match with Shirov was not wasted –

many new opening ideas were waiting their turn.

However, my absence of tournament practice had an

effect. My blitz match with Kramnik showed that

tournament atmosphere is very specific, tense, and

pressing, and it did not affect me in the best way;

moreover, many interesting ideas were ruined by

serious mistakes. I found it difficult to get to

grips with my nerves at a crucial moment.

The tournament in Wijk aan Zee was also important

because it was the first time in 13 years that my

number one position was at risk.

Anand’s brilliant tournament results made him the World Champion

in the eyes of chess amateurs and players,

if not de jure, then de facto at least.

Even my slightest failure in Wijk aan Zee,

and therefore Anand’s triumph,

could have significantly altered the flow of chess history.

Of course, I hoped to win the tournament;

reality, however, exceeded my boldest expectations.

After the first rather quick draw with Ivanchuk,

where I did not use the opportunities provided,

I still managed to win a series of games.

Never before, even in my heyday, when my rating rose to

an incredible height and reached the magic 2800,

have I managed to produce such a succession.

Ten years ago, in Tilburg and Belgrade,

I gathered +18 all together

(18 victories and 7 draws, with no defeats),

but it already seems very long ago,

and many young chess players in Wijk aan Zee regard

those results as ancient history,

like matches such as Botvinnik–Tal,

Fischer–Spassky, and Karpov–Korchnoi.

After quite a good victory over Van Wely in the second round,

there was a blitz tournament that inspired me to 7 victories in a row, even 8,

including blitz. Before that, 5 victories had been my limit,

and the 6th game had usually ended in a failure.

This time I played my 6th game with A. Shirov.

However, let us leave aside this

introduction. So, it is January 20, 1999, the

fourth round. A big chess family has gathered in a

huge hall in a small Holland village, Wijk aan Zee,

at the seashore where the wind is always blowing.

The world top chess players have gathered, along

with Grandmasters in the B tournament, and

participants in various opens. The atmosphere is

unusual, or, rather, I have become estranged from

it. Nothing predicted anything unusual that day: of

course there was blitz, then seven victories

running, and there was a good victory over A.

Yermolinsky in the ending among them.

That is why I started the game with Topalov in high spirits.

Now it is hard to say if I was waiting for something

special, though I had some strange premonitions.

I had experienced similar feelings several times

before: I was overwhelmed with emotions when I

played Karpov in Linares, and then in the next

round when I played Gelfand. Both these games ended

in brilliant victories, but this time my feelings

were somewhat different.

Kasparov – Topalov

[B07]

Wijk aan Zee, 1999

1.e4

Nothing betokened a storm

when I made this move.

Topalov, who is always eager to fight whether he has Black or White,

whoever he plays, answered with

1…d6

I was sincerely surprised.

The Pirc-Ufimtsev Defense is not a usual one for

Topalov, and this opening is hardly worth using in

the tournaments of the highest category. White has

too many opportunities to anybody’s liking, being

able to choose a sharp or a positional game; there

are various ways of developing the initiative.

Nevertheless, Topalov obviously counted on

surprise, thinking that I would play worse in a

situation I was not ready for. Besides, he hoped to

avoid my opening preparation, which he had faced

before.

2.d4 Nf6 3.Nc3 g6

This was when I began to

think. I was actually sunk in thought on the third

move, I had often played 3.f3, threatening to

transpose into the King’s Indian Defense. However,

this opening couldn’t scare Topalov off, as he was

used to it; moreover, that was what he would have

predicted. That is why I decided to play for a

position I had a definite idea about but had never

met in practice and, frankly speaking, had never

seriously analyzed.

4.Be3 Bg7 5.Qd2 c6

As far as I know, Black

usually plays c6 and b5 before the move Bg7, but I

don’t think that this shift makes a serious

difference.

6.f3

It was also possible to play

6.Nf3 b5 7.Bd3. Objectively, that may have been a

better alternative, but on this occasion both

adversaries were relying not on preparation,

but on common sense.

6…b5 7.Nge2

A strange move. If White

wanted to play 7.Bh6!?, he could do it at once,

leaving the e2-square free for the other Knight and

providing an opportunity to develop the other

Bishop on d3. Theoretically, this Knight could move

to h3 one day. Generally speaking, the move Nge2

makes no sense; its motive is purely psychological.

I remembered a conversation from before the game.

When we discussed the strategy with Yury Dokhoian,

he said, suddenly looking through Topalov’s games,

“You know, Garry, he does not like it when the

opponent makes moves he cannot predict. This

affects him strangely.” That is why I played 7.Nge2

and surprised Topalov. This move does not contain

any threats, but continues development. However, it

seemed to me that he did not like the character of

the fight, as it did not correspond to the ideas he

had before the game.

…Nbd7 8.Bh6

Better late than never. It is

useful to exchange the Bishop.

8…Bxh6 9.Qxh6

White has achieved some sort

of success, since Black cannot castle short.

However, this achievement is rather ephemeral,

because the King can hide on the Queenside as well.

White’s King will also castle there. A war of

maneuver looms, and White cannot count onsignificant gains.

Actually, if Black plays actively with 9…Qa5,

then White can move 10.Nc1, and then the Knight moves to b3, gaining a tempo.

White will manage to stabilize the game and he will

deprive Black of the opportunity to take advantage

of the diversion of the White Queen to h6.

9…Bb7 10.a3

I did not want to castle at

once, because it was not clear how to defend the

King after the Queen moves to a5 and threatens b4.

That is why White makes a wait-and-see move that

prepares long castling and holds Nc1 in reserve to

repulse the b4 threat if Black moves …Qa5.

10…e5

Topalov, after thinking for

11 minutes, decided to strengthen the position in

the center and to prepare to castle long.

Black had alternative plans, but this one looked most logical.

11.0-0-0 Qe7

12.Kb1

White did not have a lot of

opportunities either; he had to unravel the tangle

of his pieces. That was why I decided to transfer

the Knight to b3, taking advantage of the fact that

now Black’s attempt to play actively with a7-a5

would be repulsed: 12…a5?! 13.Nc1 b4 14.dxe5!

dxe5

(14…Ng8 15.Qg7 Qxe5 16.Qxe5+ dxe5 17.Na4 ) )

15.Na4 bxa3

16.b3

12…a6

It was probably possible to

castle at once, but Topalov defends his King from

the potential threat of d5 just to be on the safe side.

I doubt that this threat was that real, but Black found this move desirable.

13.Nc1 0-0-0

14.Nb3

The development of both sides

is coming to its end. However, Black has to show

some enterprise, as he is under some pressure. If

White develops with g3, Bh3, and Rhe1, then it

won’t be easy for Black. Black’s King is slightly

weakened and, of course, he should have considered playing c6-c5,

but then White would have a choice:

close the position by playing d5, or even to exchange.

It is probably more promising to close the center.

White’s space advantage lets him push for an

attack. Then I hoped to make use of Black’s

weaknesses on the Queenside. It was possible to

move the Queen from h6 to b6 or to a7.

This was an absurd thought:

it flashed across my mind and immediately disappeared,

but subconsciously I formed the idea that the Queen on b6

together with the Knight on a5 could make a lot of trouble,

especially if the White Bishop appears on h3.

This did affect the calculation of variations, but,

the mere fact that such an idea surfaced served as

a prologue to a wonderful combination.

14…exd4!

A very good decision: relief

in the center. Taking advantage of the fact that

White is a bit backward in development, Black does

not hesitate to open the game and relies on the

possibility that active pieces will compensate for

the weakened position of the King.

15.Rxd4 c5 16.Rd1 Nb6!

A good move.

Black prepares d6-d5, and I had to think hard for 10 minutes.

What does White do next?

Let’s say if 17.a4?!, then

Black gets a good position after 17…b4 18.a5 bxc3

19.axb6 Nd7.

And in case of 17.Na5 d5

18.Nxb7 (18.g3

d4) 18…Kxb7 19.exd5

Nbxd5 20.Nxd5 Nxd5 21.Bd3 f5 22.Rhe1 Qc7 23.Bf1 c4,

we have a complicated position with mutual chances.

Of course, the Black King is out in the open, but

the White Bishop is hemmed in by the pawns. Black

is sound in the center, and it is most likely that

the position is in a state of dynamic balance.

Now we already have the dim contours of a

combination. I still could not imagine how it would

look, but I realized that the moves g3 and Bh3

could not be bad.

17.g3

Now the Bishop will move to

h3, the Queen will return to f4, the Knight will go

to a5, and the blow will take place somewhere in that area.

At that moment, however, I did not know

exactly what this blow would be like. Nevertheless,

the idea of placing the pieces in such a way

already reigned over my mind.

17…Kb8

Topalov thinks that he has

some time and can calmly prepare for d6-d5.

18.Na5 Ba8 19.Bh3 d5

So, both sides have fulfilled

their plans: White has finished developing, and

Black has played d6-d5. It is important to note

that if Black had not played the Knight to a5 on

the 18th move, but had immediately played Bh3, then

the White Knight would not have reached the

a5-square after …Nc4.

Though, generally speaking,

there was such an opportunity and it was possible

to play Rhe1, but that would have been another game.

I tried to systematically fulfill the plan

that I expected to end in a sacrifice.

The move 24.Rxd4 was already clear in my mind,

though I had not yet realized the possibility of a

draw by repetition of moves. I just saw the outline

of an attack.

20.Qf4+ Ka7 21.Rhe1

This was when I saw the

possibility of a draw. Moreover, I felt that there

was a possibility to continue the game, to play

without the Rook, though I could not imagine what

it would lead to. However, the image of the Black

King on a5 comforted my heart and intuition given

to every man from birth.

The intuition of an “attacker” (let’s call it that), told me that there

would be a decision and a mating net around the

Black King would be spun in spite of the huge

material advantage of the adversary.

Besides, I was whipped up by curiosity about the

unexplored. Will there ever be another opportunity

to lure out the Black King into the center of my

own camp!? In the long run, Lasker’s ancient game

with a sacrifice on h7 and King’s move g8-g1 is like a myth to us.

Such a thing could happen only in those distant

times, we assume. And suddenly, this opportunity!

Topalov looked quite confident. He played

21…d4

Certainly, after 21…dxe4?

22.fxe4 the game is open and now the threat 23.Nd5

gives Black a lot of trouble: The Black King is too weak.

White, of course, could have played 22.Na2, but

after 22…Rhe8 or h7-h6, the game would have

become very complicated.

So naturally, my hand led the Knight to the center.

22.Nd5

Frankly speaking, this move

is not the strongest, but it serves as a prologue

for a further combination.

22…Nbxd5 23.exd5 Qd6

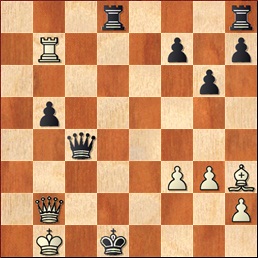

White to move |

It seemed to me that Topalov

was a bit surprised, as he thought that attacking

resources had dried out. A check on c6 was

senseless, the Knight will be beaten, the King will

go to b6, and there is hardly any opportunity for

White to move his Rooks toward the Black King. The

d4-pawn safely protects the d-rank, and there are

no squares for intrusion on the e-rank. Actually,

this was not quite right, and my next move, made

without any hesitation, turned out to be an

unpleasant surprise for Topalov.

24.Rxd4!!

When I made this move,

I saw only the repetition of the moves and the

opportunity to continue the attack, though the

whole picture of the combination was not yet clear.

I already saw the idea Rd6-Rb6, but I still could

not get rid of the thought that all lines should be

checked to the very end. Maybe Black will find some

opportunity for defense. Topalov spent about 15

minutes thinking. I walked around the hall –

rather, I fled – and at these feverish

moments it seemed to me that there were very few

participants and that most of the games had already

been finished. My mind worked only in one direction,

and one of these moments brought me the

image of the whole cluster of various lines.

I saw the move 37.Rd7. I don’t even remember how this

line was formed in my head, but I saw the whole

line up to the end. I saw the journey of the Black

King after 36.Bf1, 37.Rd7 and I could no longer

suppress my excitement, because at that same moment

I realized that the move 24…Kb6 ruined the whole construction.

I was intending to play 25.b4, as I underestimated

the fact that after 25…Qxf4

(25…Nxd5 26.Qxd6+ Rxd6

27.bxc5+ Kxc5 28.Nb3+ Kb6 29.Kb2 Rhd8 30.Red1 Bc6

31.f4 Kc7 ) )

26.Rxf4 Nxd5 27.Rxf7 cxb4

28.axb4 Nxb4 29.Nb3 Rd6 Black’s position is better.

Maybe, if Topalov had played 24…Kb6!

(24…Bxd5?! 25.Rxd5 Nxd5

26.Qxf7+ Nc7 27.Re6 Rd7 28.Rxd6 Rxf7 29.Nc6+ Ka8 30.f4)

then I could have found the

move 25.Nb3!, which again makes it impossible to

capture the Rook: 25…Bxd5!

(25…cxd4? 26.Qxd4+ Kc7 27.Qa7+ Bb7

28.Nc5 Rb8 29.Re7+ ; ;

25…Nxd5? 26.Qxf7 Rhf8 27.Qg7 Rg8 28.Qh6 Qf8 29.Rh4 ) )

26.Qxd6+ Rxd6 27.Rd2 Rhd8

28.Red1 and White keeps equality, but not more.

The mere thought that I could spoil such a

combination drove me crazy, and I only prayed that

Topalov would capture on d4. I still was not sure

that this would win, but the beauty of the

combination I saw impressed me. and White keeps equality, but not more.

The mere thought that I could spoil such a

combination drove me crazy, and I only prayed that

Topalov would capture on d4. I still was not sure

that this would win, but the beauty of the

combination I saw impressed me.

I could not believe my own eyes when Veselin

twitched abruptly and grabbed the Rook. As he

explained after the game, he was exhausted by the

tense fight and he thought that White would have to

force a draw by the repetition of moves after the

Rook was captured. He saw the main idea of the

combination, but it did not occur to him that White

would play without the Rook, trying to make use of

the King’s forward position on a4.

24…cxd4?!

This move loses the game, but

it is worth an exclamation mark, as great

combinations cannot be created without partners.

If Topalov had not taken the Rook,

the game could have finished in a draw:

Veselin would have had half a point more,

I – half a point less.

He would have win a little bit,

I would have lost a little bit,

but chess and chess amateurs would have lost a lot.

However, Caissa was kind to me that day…

I do not know what I was rewarded for,

but the development of events became forced after the capture on d4.

25.Re7+!

I made this move with

lightening speed. And there was nothing to think

about. The Rook was inviolable. Such moves are

always made with pleasure, and all I have said

before (that the d-rank is closed by the d4-pawn

and that there are no squares for intrusion on the

e-rank) turned out to be ruined.

Two White Rooks sacrifice themselves, and thus,

the way to the Black camp is opened for White’s pieces.

The construction I dreamt of – Queen on b6,

Knight on a5 – has suddenly come true,

because of the Bishop on h3.

If Black moves 25…Kb8?,

then after 26.Qxd4! Nd7 27.Bxd7 Bxd5 28.c4! Qxe7

29.Qb6+ Ka8 30.Qxa6+ Kb8 31.Qb6+ Ka8 32.Bc6+! Bxc6

33.Nxc6, Black loses by force.

I have to note that 25.Qxd4? did not achieve the goal,

because of 25…Qb6 26.Re7 Nd7

and White’s attack fades away.

25…b6 26.Qxd4+ Kxa5

Some of the participants, including Anand,

asserted that the move 26…Qc5 saved the game.

However, after 27.Qxf6+ Qd6 28.Be6!! White closed

the rank but left the opportunity to vary threats

and to force Black into a desperate position.

For example, 28…Bxd5

(28…Rhe8 29.b4! )

29.b4! Ba8 30.Qxf7 Qd1+ 31.Kb2 Qxf3

32.Bf5 would be the simplest way,

as all the lines are closed and mate threats become inevitable. )

29.b4! Ba8 30.Qxf7 Qd1+ 31.Kb2 Qxf3

32.Bf5 would be the simplest way,

as all the lines are closed and mate threats become inevitable.

27.b4+ Ka4 28.Qc3

I made the last move without

hesitation. Frankly speaking, I could not make

myself think as I strove for the end.

I already saw it, and it seemed to me that it was

the way to finish the game, that Black could not avoid it,

and that there were no other defenses.

Veselin gave me time when he was thinking himself,

but I could not make myself look for another opportunity.

My hopes were in vain! However, it is difficult to judge.

It seems to me that the beauty of this combination is not

inferior to any alternative.

Though, in order to be objective from the point of

view of chess truth, it would be stronger to play 28.Ra7!

This move was found by Lubomir Kavalek,

probably with the help of a computer, as it is impossible

to look through all the lines independently.

Nevertheless, the idea found by Kavalek provided the opportunity

to realize all problem motives in a clearer way,

keeping Black from using new defensive resources.

Such resources could appear in the game as played,

though, frankly speaking, they were not enough.

So, after 28.Ra7, both captures on d5 lose quickly:

28…Nxd5 29.Rxa6+!! Qxa6 30.Qb2 Nc3+ 31.Qxc3 Bd5 32.Kb2

|

Black to move |

and we approached the position

when there was no defense from the threat of Queen’s self-sacrifice on b3.

Black cannot attract another piece to control the a2-g8 diagonal,

as the White Bishop controls the e6-square.

The Bishop’s capture on d5 also loses:

28…Bxd5 29.Qc3 Rhe8 30.Kb2 Re2.

Black linked the c2-pawn and defended from the Qb3 threat.

And here the Queen suddenly changes its route –

31.Qc7!, threatening a mate from a5.

And after 31…Qxc7 32.Ra6 the King turns out to be mated

by the White Rook. A wonderful scheme of mating pieces!

The strongest move, as in the game itself, is 28.Ra7 Bb7 29.Rxb7 Qxd5.

(After 29…Nxd5, White finds

a new mating construction, 30.Bd7!, threatening

with Bxb5+ to expose the Black King and to mate it

again with the Rook, and after 30.Rxd7 White varies

the threats by the move 31.Qb2, threatening a mate

from b3. The only move is 31…Nxb4,

and then 32.Rxd7 attacks the Queen again.

And there is a mate from b4 after 32…Qxd7. 32…Qc5 33.Rd4

threatens to capture on b4 and on h8.

After 33…Rc8 White plays 34.Qb3+ Ka5 35.ab,

and Black suffers crucial material losses.)

The continuation after 29…Qxd5: 30.Rb6

a5.

(In case of 30…Ra8, White

restores the material balance after 31.Qxf6 and

continues the crucial attack. 31…a5 32.Bf1 Rhb8

33.Rd6 driving away the Black Queen and the White

Queen comes back and mates.)

It seems that after 29.Rxb7 Qxd5 30.Rb6 a5 31.Ra6,

Black can defend himself playing Ra8,

but then a sudden change in mating construction follows: 32.Qe3!!

Right here, as after 32…Rxa6 goes 33.Kb2 (which

threatens mate on b3), and after 33…axb4 34.axb4

the a3-square is open for a new mating construction.

A capture on b4 postpones the mate by one more

move. 35.Qc3 Ka4 36.Qa3 checkmate.

The only defense is 34…Qa2+ 35.Kxa2 Kxb4+ 36.Kb2.

Black has rather good material – two Rooks

for the Queen – but White continues the

attack and there is no escape from it: 36…Rc6

37.Bf1, threatening a mate from a3. 37…Ra8

38.Qe7+ Ka5 39.Qb7. A mate threat on b5 results in

the win of the Rook.

28…Qxd5

Here, Topalov had less

than half an hour, I had 32 minutes.

It would be even weaker to play 28…Bxd5, because

of 29.Kb2! with inevitable mate.

29.Ra7! Bb7 30.Rxb7

White refuses the last opportunity to force a

perpetual check by playing 30.Qc7.

I was sure that White would achieve more.

Of course, 30…Rd6 31.Rb6! is an effective

variant, but not very complicated. The Black Rook

on d6 cannot do two things simultaneously: defend

the a6-pawn and control the d4-square, as Black has

to play …Qd4 after Kb2.

It is important that there is no checkmate on d1,

because the White King suddenly goes to a2 and it

turns out that the threat Qb3 can be also supported

by the King from the a2-square.

That is why the Black Queen has to be on d5

(one has to understand this very important moment),

in order to control the b3-square and to be able to play …Qd4

if the White King is on b2. Therefore, the Rook should be on d8.

It leaves enough opportunities for most various problem motives

that are more vivid in this particular line.

Both adversaries saw the line, and Topalov,

having spent some of his precious minutes, played

30…Qc4

This is the most natural

defense, and I counted on it, too. Moreover, this

is the defense that leads to the most effective

mating end that I had no rest from for the last

15–20 minutes, ever since its image

mysteriously arose in my mind.

Actually, Black had two other defenses,

and each of them could have ruined the delicate conception that I had in mind.

The first one was 30…Rhe8, the move Topalov

showed on the next day before the round started.

Thus he drove me into a tight corner in my game

with Reinderman, where I was deep in thought

calculating various lines after 30…Rhe8 and, not

being able to find the way out, I was very careless

in the opening, making two slips and mixing

everything up. Fortunately, I rethought quickly,

got rid of all these fixed ideas and nightmares

and played a marvelous game.

However, Topalov’s idea was not likely to live a long life,

because everyone was interested in this game and

the statement that the move 30.Rhe8 could refute

White’s brilliant composition must have caused inward protest.

So, at the end of the round,

Ligterink proudly showed a brilliant victory for White.

Thus, White plays 31.Rb6 Ra8. It is important to

note that the move 32.Be6, which suggests itself,

does not achieve the goal: 32…Rxe6 33.Rxe6.

And Black, of course, can not capture the Rook on e6,

as after Kb2 there is no defense from the mate, but

plays 33…Qc4. This is the very counter-sacrifice

that I told you about. White has to beat c4:

34.Qxc4 bxc4 35.Rxf6 Kxa3 and then 36.Rxf7 Re8

Black starts a counter attack and, strange as it

may seem, keeps good chances to win the ending.

White cannot allow such exchanges and, as we can

see, the c4-square is now crucial. Black could

change the defense, playing 30…Rhe8. In this case

one Rook would defend the a6-pawn from a8, and the

move Kb2 faces Qe5. The Rook controls the

e5-square, and the Queen is ready to move to c4.

That is why the key move is 32.Bf1!! Objecting to

Qc4, White creates a quiet threat Rd6,

which is crucial in the case of 32…Nd7.

(32…Nd7 33.Rd6! Rec834.Qb2)

If 32…Re6, then White simply makes

an exchange on e6 and plays 34…Kb2.

If 32…Red8, White plays 33.Rc6 and creates a

threat Rc5, now we have Rd6 anyway after 33…Nd7,

as the d-rank is closed.

And after 33…Nh5, we can, for instance, play 34.c5 Rac8 and 35.Kb2.

And there is no way out again!

Ligterink, most likely with the help of a computer,

found a unique defense. This is a counter-sacrifice

that faces a marvelous, though probably also

computer, denial.

This is 32…Re1 (after 32.Bf1) 33.Qe1 Nd7.

The White Rook is captured, but the most important

thing is that the Black Knight tries to go to b6

and after 34.Qc3 Nb6 35.Kb2 this Knight checks the

King from c4, after 36.Ka2 he checks the King from d2,

controls the b3-square, and suddenly Black wins.

However, after 33…Nd7 White makes a diverting

Rook sacrifice – 34.Rb7!

It is necessary to take the Rook, as after 34…Ne5

35.Qc3 Qxf3 the easiest way to the victory would be

36.Bd3 Qd5 37.Be4.

And after 34…Qb7 there is that very computerlike

ending: 35.Qd1 Kxa3 36.c3 and the White Queen mates

in a stair-like way Qc1-Qc2-Qa2. Checkmate is inevitable!

I do not know if it would be possible to find this line during a game,

but the beauty of the combination is absolutely irresistible.

In essence, we deal with a problem of changing mates,

which, as far as I can remember,

have never been practiced by serious chess players.

Such interchange of mates is characteristic only of special chess problems.

Black has another counter-opportunity: he can make

a sudden Knight sacrifice 30…Ne4! and after

31.fxe4 Qc4 the idea becomes clear – if White

follows the line of the game absent-mindedly, then

after the move Bf1 at the very end of the line,

Black will capture on e4 with check. The difference

is that the White pawn moves from f3 to e4 and now

this square is clear for the Black Queen.

Of course, White does not have to play 31…Qc4

– 32.Qf6, though after 32…Kxa3 33.Qxf6 Kxb4

34.Bd7, he is not at risk. The game, however, would

end in a draw.

The move 32.Qe3? is not promising either.

Black plays 32…Rc8, which is the same

counter-sacrifice, 33.Bxc8 Rxc8, approaching the

counterattack: 34.Qc1 Qd4! – the best way.

And White has accept a draw.

A capture on c4 gives Black chances to win and

leads to a complicated ending: 32.Qxc4?! bxc4

33.Kb2. The best move is 33…f5 and after 34.exf5

Black has to play …c3+ and give an intermediate checkmate

(as after 34…Rd6 35.fxg6 c3+

White plays 36.Ka2 hxg6 37.Bf1, and we come across mating

constructions once again: either Bc4-Bd3, or Bb5-Ra7).

However, after 34…c3+ 35.Kxc3 Kxa3 36.f6 Rd6

37.f7 Rc6+ 38.Kd4 Rxc2 39.Bf1 White has some chances to win.

Maybe he will win the ending because of a strong pawn

and the opportunity to push the King to g7.

However, White didn’t start this combination to win the ending.

Fortunately, adetailed analysis shows

that White has a better opportunity.

After 30…Ne4 31.fxe4 Qc4 the right move would be

32.Ra7 as it threatens mate on a6 again.

Now, after 32…Ra8 White wins playing 33.Qe3,

in order to play Kb2 after Ra7.

And after 32…Rd1+ 33.Kb2 Qxc3+ 34.Kxc3 Rd6

we come to an ending, but this ending is different from the previous one.

The Black King is still threatened with mate.

The pawn has not yet left the b5-square and White can

continue forcing threats, in spite of the

disappearance of the Queens: 35.e5 Rb6 36.Kb2

Re8 (where else? If

36…Rd8, then 37.Bd7)

37.Bg2! in order to play 37…Rxe5

38.Bb7, and then 38…Re7 39.Bd5, and suddenly the

Bishop gets at b3. As we know, the result would be

just as if the Queen were there.

Thus, after 37.Bg2! Rd8 Black controls the

d5-square, and then 38.Bb7 Rd7 39.Bc6!!

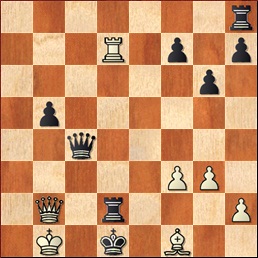

|

Black to move |

Now, after 39…Rd2 the move

40.Be8 will decide, and after 39…Rd8 40.Bd7 we

reach the position in question.

Black is paralyzed and can do nothing but wait for

a disgraceful end.

31.Qxf6 Kxa3

Topalov still erred in thinking

that White had nothing better than 32.Qxa6 Kxb4 and 33.Bd7.

Really, White has no other possibilities

as the King is under the threat of mate himself.

Black misses the best defense that let him continue

the resistance in the ending by playing 31…Rd7+!

And then 32.Kb2 Ra8 33.Qb6! threatening

a mate from a5. 33…Qd4+

(At 33…a5, 34.Bd7 is decisive)

34.Qxd4 Rxd4 35.Rxf7.

Technically, it is the most complicated decision.

Black must play 35…a5 36.Be6 axb4 37.Bb3+ Ka5 38.axb4+,

and it turns out that the Rook cannot capture on b4

because after c3 this Rook is trapped and the

ending is technically won. Then, after 38…Kb6

39.Rh7 Rc8 40.h4 White can win this position

without much trouble. The Bishop and three pawns

are much stronger than the Rook. White’s setup is

marvelous and his victory is a matter of time.

However, the continuation 35.Bd7 was more

effective, and I counted on it during the game

because, frankly speaking, I did not see that after

38.axb4+ Rxb4 the move 39.c3 trapped the Rook.

I planned to play 35.Bd7. Analysis showed that this

was also enough for the victory. White tries to

dominate, to press the Black pieces, and he

prepares to move the Kingside pawns, taking

advantage of the fact that the Rook should be on

a8. Black tries to defend himself from Bb5+ and not

to let the Bishop go to b3.

Nevertheless, he does not succeed.

After 35.Bd7!? Rd2 36.Bc6 f5 37.Rb6 Ra7 38.Be8 Rd4

39.f4. Black is nearly stalemated.

After 39…Rc4 40.Bf7 Rxb4+ 41.axb4 Rxf7 42.c3 Ra7,

the only way is to play 43.Re6 a5 44.Re1,

and we come across a new mating construction.

This time it is a checkmate from a1;

the Rook mates the Black King on the a-rank.

Nevertheless, Topalov took on a3 with the King, and

the line I dreamt of came true!

Once again, tried to check the lines, and, afraid

to believe my own eyes, I made sure that what I had

thought of for so long was just about to happen.

It seemed to go on for ages, but in fact, it took not

more than two minutes.

Then followed

32.Qxa6+ Kxb4

|

White to move |

33.c3+!

Probably, this was when

Topalov realized everything.

Of course, he saw the move 36…Rd2 and then,

as it often happens to chess players,

he immediately saw Rd7. Black has no choice,

he has to take with the King on c3.

33…Kxc3 34.Qa1+ Kd2

There is no way back: If

34…Kb4 35.Qb2+ Ka5 36.Qa3+ Qa4 37.Ra7, winning

the Queen.

35.Qb2+ Kd1

The Black King has made the

way to his Calvary – from b8 to d1 –

across the whole chessboard! And when it seems that

he has reached a quiet harbor (White has no more checkmates),

the Bishop, which was on h3 and did nothing but shot

in the emptiness and defended the e6 square,

made his move.

|

Black to move |

36.Bf1!

White attacks the Queen, who cannot escape.

If he retreats along the e-rank the move 37.Qe2 and checkmate would follow,

and retreat to e6 will allow a mate from c1.

Another change of mating constructions!

In fact, we should not forget another opportunity:

instead of 35…Kd1, 35…Ke3 can be played,

then the continuation would be 36.Re7+ Kf3 37.Qg2.

This is one more of the innumerable mating endings.

Thus, after 36.Bf1 the Bishop is also inviolable,

as after 36…Qxf1 37.Qc2+ Ke1 38.Re7+.

– I don’t know who would like such a mate.

This is a trifle in comparison with all we had before.

36…Rd2

Black makes a counterblow and

for another second it seems that the worst is left

behind, because White seems to have no more

resources.

36…Qc5 37.Qe2 mate; 36…Qe6 37.Qc1 mate.

With one more second to rest, Black will announce

checkmate to the White King himself.

But this is where the White Rook enters.

37.Rd7!

The weakness of the a1-h8

diagonal is the most important element of this

combination. Usually everything depends on such trifles.

If only the Black Rook had been on g8,

there would have been no combination at all…

And after 37.Rd7 Black has nothing else to hope for.

However, Topalov still continued the fight mechanically.

Black has to take the Rook on d7.

37…Rxd7!

|

White to move |

38.Bxc4 bxc4 39.Qxh8 Rd3

This moves gives the illusion

of activity. If White suddenly takes on h7, then

after c3 Black will queen the Black pawn.

But we did not play draughts,

it was not obligatory to capture,

and now the Queen could show her true strength.

40.Qa8

Moving closer to the battlefield.

40…c3 41.Qa4+ Ke1 42.f4

And thus Black is deprived of

the last hope to get a position of “the Rook

against the Queen” that demands a certain accuracy

from the strongest side, if playing a computer.

And still, as practice has proved, a weaker side in the

battle of two chess players is not able to resist,

as it is nearly impossible to make a “computer

move” that would take the Rook away from the King.

However, it is not necessary to know all these nuances.

White keeps a lot of pawns so that Black could hope to win them sometime.

42…f5 43.Kc1

Neutralizes any Black’s hope connected with c-pawn.

43…Rd2 44.Qa7

The Queen starts attacking

Black pawns, and the h2-pawn is inviolable because of Qg1+.

Topalov resigned, and this wonderful game was over.

In

actual fact, the game was not over, as its transmission

via the Internet shook the world of chess, and the

game itself was analyzed. Topalov analyzed the game

at night, then it was analyzed the following day by

Dutch journalists. They looked for defenses,

counterblows, found the way to win, and then

studied the defense again. A great many articles

were written on the game. Later on, Kavalek will

find the move 28.Ra7, but we now know the final

verdict, which was announced several days after the

game was played, during the tournament in Wijk aan

Zee. Dozens or even hundreds of computers had

already analyzed the game and confirmed that

White’s combination was correct and Black’s

decisive mistake was 24…cxd4,

which cut off all ways for rescue.

After that the Black King was doomed to cross the road

of death and White, fortunately, unless Black found hidden defenses,

ended the game with two strokes – 36.Bf1 and 37.Rd7.

Indeed, from now on, it will be very

difficult for me to say that my best game has not

been played yet. From the professional point of

view, I believe that my game with Svidler is even

better, but chess amateurs do not care about the

Grunfeld defense! Chess amateurs do not care about

a pawn sacrifice in a famous position, or about a

piece counter-sacrifice. They don’t care about the

few possible moves with centralization of pieces or

about the transfer of the Queen, when one can enjoy

the combination and see the romantic appeal of

a modern chess game with a good opening and an

interesting fight, when there is a certain

romanticism that seemed to have fallen into

oblivion. And it seems appropriate that such a game

was played in an unpretentious and not very

expressive line. As I have already said, both

adversaries played according to their common sense,

driven by their own understanding and judgment and

not by some special knowledge. I suppose that one

can hardly find a better example to debunk a

popular myth, that all my success is, to a certain

extent, connected with straightforward opening

preparations. In the long run, true chess

connoisseurs realize that the secret of success

does not depend only on intensive preparation but

on the way this preparation is transformed within

the chessplayer, in the way it lets him develop his

chess horizons. Ω

|

|