Edward Winter

The Encyclopaedia of Chess Middlegames (Chess Informant, Belgrade, 1980) was appropriated by Eric Schiller in his volume The Big Book of Combinations (Hypermodern Press, San Francisco, 1994). It is customary for writers of such works to ‘borrow’ widely from each other, but Schiller went far beyond that. He plundered hundreds (many hundreds) of positions, and gave himself away by indiscriminately repeating countless mistakes from the earlier tome.

Before turning to the facts of the case, it is worth bearing in mind Schiller’s version of events, from his Preface (page 3):

‘The combinations include most of the most famous and well-known examples, but there are also many positions taken from rare and unexplored literature. You are sure to find many combinations you have never seen before, no matter how many books you have studied.’

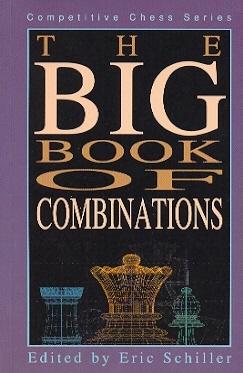

The Big Book of Combinations presents the positions in chronological order, and we opened it, at random, at pages 150-151. Schiller offers 12 positions there from games played in 1978 or 1979.

So how many of them had appeared in the Encyclopaedia? Answer: all 12 of them. Moreover, five of the positions are given no venue by Schiller beyond a mere ‘Soviet Union’. Why? Because that is all the Encyclopaedia gave.

Clearly, a more extensive spot-check was required. We therefore turned back to page 17, where the twentieth-century positions begin, and went through them until around the end of the Second World War (page 38). That accounted for 132 positions. Astoundingly, it emerged that all but about half a dozen of them had been lifted, without a word of credit, from the Encyclopaedia. Elsewhere in Schiller’s book, we discovered, it was the same story. Realizing that none of the positions from the 1950s had yet been scrutinized, we invited a colleague (who possesses neither book) to pick any year from that decade. He chose 1958, and we duly informed him that a) for that year Schiller gives 13 positions, and b) all 13 had appeared in the Encyclopaedia.

On page 200 of the May 1985 BCM we referred to the unreliability of the Encyclopaedia and pointed out, inter alia, that it wrongly gave Capablanca’s game against Fonaroff as played in 1904 instead of 1918, while the Cuban’s win over Mieses was dated 1931 rather than 1913. Schiller, however, was oblivious to all this, and his 1994 ‘effort’ blithely copies these and numerous other mistakes from the Encyclopaedia.

For example, the first position from our lengthy spot-check (i.e. on page 17 of Schiller’s book) is labelled ‘Schlechter – Metger, Vienna, 1899’. That is certainly what page 202 of the Encyclopaedia had also stated, but Black in that game (a famous Schlechter win) was Meitner. Indeed, two pages earlier Schiller offered a similar position and mentioned Meitner on that occasion, although the date was given as ‘1889’ and the venue was bafflingly rendered as ‘Bec’. Why? Because Schiller did not realize that Beč means Vienna in Serbo-Croat.

Page 183 of Schiller’s book states, ‘In general, we have provided first names or initials only when there might be some question about the identity of the player’, but no such effort has been made. Page 18 has ‘Lasker – Bauer USA, 1908’, i.e. exactly what the Encyclopaedia put on page 251. This leaves the reader to assume that White was Emanuel Lasker, but in reality the position was won by Edward Lasker. (His opponent was Arpad Bauer, and the position was given on page 100 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 15 March 1908.) Of course, Edward Lasker did not visit the USA until well after 1908, but there is a simple explanation. Contrary to the ‘USA’ claim in the Yugoslav book, automatically parroted by the American purloiner, the venue was Berlin, Germany.

Page 138 of the Encyclopaedia labelled a position ‘Eliskases – Mori Birmingham 1937’. Schiller (page 34) self-evidently gives the same spelling, unaware that Black was W. Ritson Morry. On the next page Schiller has this caption: ‘Kito – Shelhaut Hastings, 1938’. That, naturally, is identical to what appeared in the Encyclopaedia (page 146), but the players’ names should read Kitto and Schelfhout. Another 1938 game, on page 249 of the Encyclopaedia, was ‘Tylor – Thomas Bryton 1938’. It may seem obvious that ‘Bryton’ should read Brighton, but it was not obvious enough for Schiller; on page 36 he too uses the spelling ‘Bryton’, adding for good measure an original mistake of his own by changing Tylor to ‘Tyler’.

Schiller’s book can be dipped into on any page for more of the same. A further typical case concerns ‘Parr – Waitkroft, Netherlands 1968’, which is how the position is presented in the Encyclopaedia (page 32) and, consequently, also in Schiller’s book (page 99). Yet even a novice writer might be suspicious of a spelling like ‘Waitkroft’ or capable of identifying the players and finding the proper venue and year (i.e. F. Parr v G.S.A. Wheatcroft, London, 1938) in a very common book, The Golden Treasury of Chess by F. Wellmuth. (The exact occasion was the City of London Chess Club Championship, and Frank Parr annotated his brilliancy on page 318 of the July 1938 BCM.)

Readers who own the Encyclopaedia of Chess Middlegames and The Big Book of Combinations will see for themselves that the copying perpetrated by Schiller is so extensive that a series of further exposés of his conduct could easily be written, each with a different set of examples. There would certainly be no need for such articles to plagiarize each other.

(2965)

Two further cases are outlined here. The first concerns the Pakistan Chess Player website, where Lev Khariton presented as his own writing two articles (about Alekhine and Carlsbad, 1929) which, we pointed out in October 2001, had been lifted from pages 77 and 147 of Irving Chernev’s book Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974). It was not until April 2002 that the public protests had any effect and the misappropriated material was grudgingly removed from the website. Since being exposed, Khariton has written various attacks on our book Chess Explorations, systematically misreading, misquoting and misrepresenting its contents.

The second case was referred to by Yasser Seirawan (see page 26 of the Spring 2000 Kingpin) in the following terms:

‘Keene was caught red-handed plagiarizing copyrighted material from Inside Chess magazine for one of his potboilers [The Complete Book of Gambits].’

Before the facts are related, one little myth about Chess Notes may be dealt with here, i.e. the occasional claims that C.N. ‘repeatedly’ (or even ‘frequently’) attacks Raymond Keene. Over the past decade the column has hardly ever mentioned his name, but in the present context it is impossible not to.

Under the title ‘The Sincerest Form of Flattery?’ John Donaldson wrote an article on pages 24-25 of Inside Chess, 3 May 1993 which began as follows:

‘Examples of plagiarism are not unknown in chess literature, but Raymond Keene has set a new standard for shamelessness in his recent work, The Complete Book of Gambits (Batsford, 1992). ... Unfortunately, Mr Keene has done nothing less than steal another man’s work and pass it off as his own.

A glance at pages 128-132 of his recent book, The Complete Book of Gambits, and a comparison with my two-part article on Lisitsin’s Gambit, which appeared in Inside Chess, Volume 4, Issue 3, pages 25-26, and Issue 4, page 26, early in 1991, reveals that not only did Mr Keene have nothing new to say about Lisitsin’s Gambit, he could hardly be bothered to change any of the wording or analysis from the articles that appeared in Inside Chess other than to truncate them a bit. What’s more, no mention of the original source was given in The Complete Book of Gambits, misleading the reader as to the originality of Mr Keene’s work.

Just how blatant was the plagiarism? Virtually every word and variation in the four and a half pages devoted to Lisitsin’s Gambit in Keene’s book was stolen.’

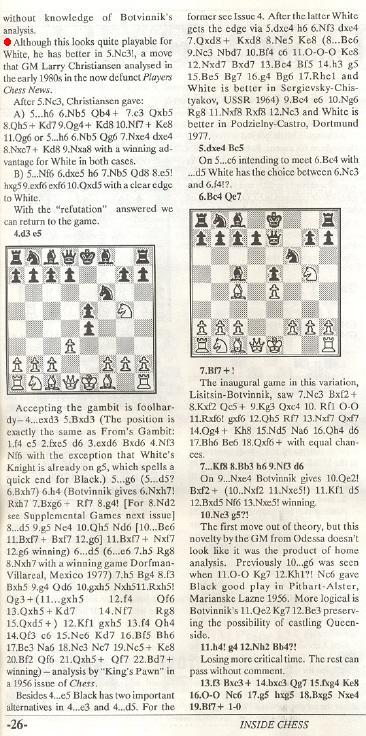

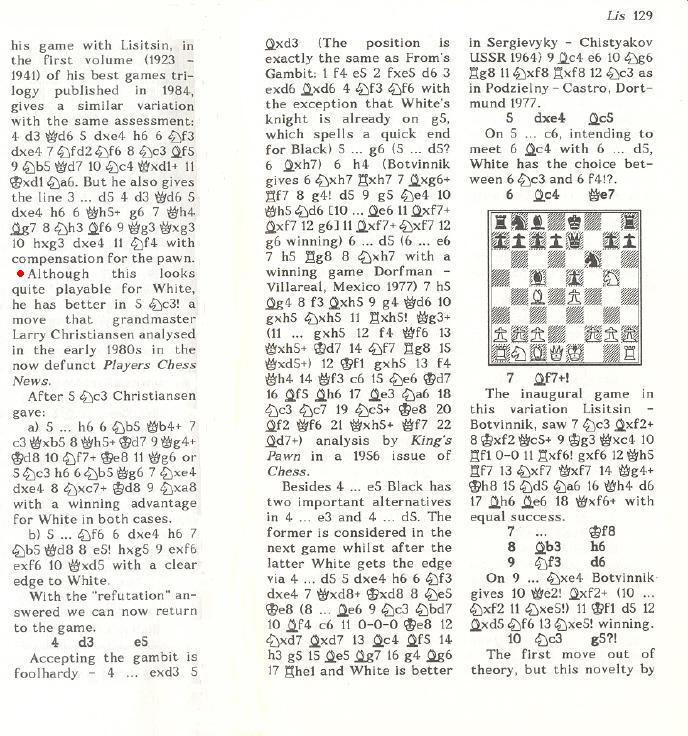

Left: part of John Donaldson’s article in Inside Chess. Right: from pages 128-129 of Raymond Keene’s subsequent The Complete Book of Gambits.

Donaldson then compared the two texts in some detail, pointing out certain discrepancies:

‘The note in The Complete Book of Gambits is exactly the same except that “with equal chances” is changed to “with equal success”. A burst of originality on Mr Keene’s part, or just Fingerfehler? More originality is seen as “Sergievsky” becomes “Sergievyky” at Keene’s hands. Perhaps he would do better to just photocopy other people’s work and print that.

Mr Keene’s behavior is absolutely inexcusable.’

On the next page of Inside Chess there was a brief exchange of correspondence between Andrew Kinsman (the then Chess Editor of Batsford) and Donaldson. Kinsman wrote:

‘I have discussed this matter with Raymond Keene who informs me that a full credit for yourself and Inside Chess was prepared with the manuscript to go into the book. However, due to an oversight on his part this became detached and failed to appear in the book. It was not his intention to publish the piece without due acknowledgment.

Mr Keene offers his full apologies for this unfortunate oversight, which will be put right on the second edition (or the whole piece dropped if you prefer). Furthermore, he is happy to offer you, or any nominated charity of your choice, a share of the UK royalties on the book equivalent to the share that the Lisitsin section occupies in the book. We hope that such a settlement will be amenable to you.’

An extract from Donaldson’s reply (published immediately afterwards) is given below:

‘I would prefer that my work be omitted from any second edition of The Complete Book of Gambits and I suspect that if all the other victims of Mr Keene’s “unfortunate oversights” are accorded the same privilege, it will be a slender work indeed. (The complete lack of any bibliography for this book is typical of Keene.)

As for your generous offer of a share of the UK royalties, I would prefer a flat payment of $50 per page ($200) be sent to me at this address.’

Page 19 of the 14 June 1993 Inside Chess featured a lengthy letter from Keene which intimated that extracting any money from him would be considerably harder than Andrew Kinsman had suggested. Keene’s letter began:

‘… First of all, I must personally apologize for accidentally printing some of your material in my book on Gambits. This book was several years in preparation and, in an endeavour to be complete, I gathered together a huge amount of source material. In order to beat a last-minute deadline, there was a certain amount of rush. In this process, one of the Chapters I had written, plus the planned notes, including your material, slipped past the net and appeared in print. Of course, I regret this and I am broadly receptive to the proposal you make in your fax of 11 May.’ [Note added by the magazine: ‘That Mr Keene pay for material lifted without credit or permission from Inside Chess.’]

However, Keene went on to claim that Inside Chess itself had printed material of his without permission and, consequently, that:

‘I propose, as the most elegant solution, that both I and Inside Chess pay $200 each to two nominated charities. Alternatively we can just call it a draw.

I leave the choice to you.’

The Keene material in question had appeared two years previously in Cathy Forbes’ report on Hastings, 1990-91. On page 19 of the 14 June 1993 issue of Inside Chess she wrote:

‘In writing my report on Hastings 1990-91, I made extensive use of Ray Keene’s notes from the Hastings Bulletin. I did have permission to use this material, but I neglected to acknowledge the source in the article, which was an error of omission on my part.’

That letter was followed by one from Donaldson to Keene:

‘I’m afraid we will have to refuse your “draw” offer. The two situations are hardly the same. You gave Cathy Forbes permission to use the material in question in her story and she, in turn, gave us permission to use it and we paid her for it. Case closed. We don’t owe you two cents, much less $200.

Since you admit that you owe us for the material you appropriated from our pages, we would appreciate payment as soon as possible, though we understand your reluctance to establish a financially dangerous precedent in this area.’

Inside Chess did not return to the subject until its 7 February 1994 issue (page 3), when a reader enquired whether Donaldson had ever received the claimed $200. The magazine reported that on 22 July 1993 Donaldson and Henry Holt and Company (‘Keene’s American publisher’) had …

‘… entered into an agreement to settle all claims arising out of Henry Holt and Company’s distribution of The Complete Book of Gambits … Henry Holt and Company agreed to pay Mr Donaldson an undisclosed amount, and agreed to refrain in the future from distributing copies of the book that contained the allegedly infringing material.’

At the Chess Café Bulletin Board on the Internet (a posting dated 30 May 2001) Keene provided another explanation of his conduct over the Gambits book (quoted in full below):

‘I left for a foreign trip while this book was being typeset and accidentally left a complete copy of the Donaldson article with the manuscript. It was a very minor sideline – hardly worth the pages that ended up being devoted to it when the typesetter dutifully put the whole article in! (1 Nf3 f5 2 d3 Nf6 3 e4 I think it was.) I did not agree to pay any damages – Batsford decided unilaterally that this was the simplest solution.’

We add that the book (on the imprint page) thanked ‘Byron Jacobs for his speedy and efficient typesetting’. It is also interesting to note from the above passage that even as late as 2001 Keene appeared unaware that Lisitsin’s Gambit begins 1 Nf3 f5 2 e4.

The remaining question is the extent of the ‘simplest solution’, i.e. the size of the damages which eventually had to be paid out because of Keene’s conduct. The amount of the final settlement was not the $200 which Donaldson had originally sought. It was $3,000.

(2966)

A number of additional cases are listed here pro memoria:

Chess (Basics, Laws and Terms) by B.K. Chaturvedi copied extensively from Chess Made Easy by C.J.S. Purdy and G. Koshnitsky (see A Chess Omnibus, pages 335-337).

Coles Publishing Company pirated editions of books by Capablanca, Marshall, Reinfeld, Rice and Love (see A Publishing Scandal).

Postings at the Chess Café’s Bulletin Board in 2001 (most notably by Paul Kollar) pointed out many passages published under Larry Evans’ name which were identical or similar to what had appeared in books by Lasker, Réti, Reinfeld and Fine. (Regarding Fine, on page 32 of the February 2002 Chess Life Evans defended himself by affirming that he had collaborated on The World’s Great Chess Games and had himself written the passages in question.)

The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia by N. Divinsky copied many entries from The Encyclopedia of Chess by H. Golombek. Despite that, the Divinsky book was billed by the publisher as ‘completely new’.

On pages 8-9 of the 5/1986 New in

Chess (see also the account on pages 278-279 of Kings,

Commoners and Knaves) Christiaan Bijl related how his volume on

Fischer’s games had been abused by Dimitrije Bjelica.

(2971)

Afterword: See also C.N. 4108, regarding Bjelica’s plagiarism of Irving Chernev. Moreover, C.N. 2888 reported on how Sadoscacchi by F. Pezzi and M. Diversi (Rome, 1994) had copied from Chernev’s The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played (New York, 1965); see pages 228-229 of Chess Facts and Fables. For further examples, involving ‘Philip Robar’, see the references in the Factfinder.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.