Edward Winter

(1999, with updates)

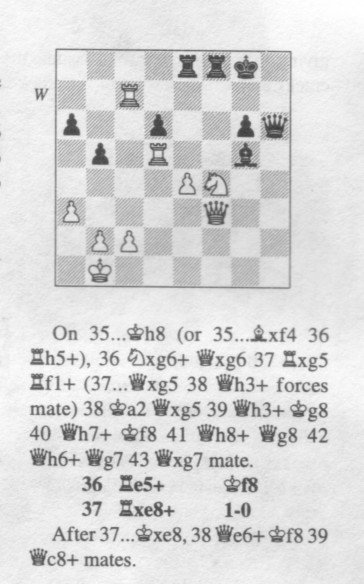

‘It’s a great book without a doubt, and can go straight on the shelf alongside Alekhine and Tarrasch and fear no comparisons.’ That was the opinion of W.H. Cozens in a review (December 1969 BCM, pages 370-371) of Bobby Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games, published by Simon & Schuster in the United States and by Faber and Faber in the United Kingdom. The book continued to receive the highest plaudits from chess enthusiasts of all levels throughout the world, but then came disaster; in 1995 B.T. Batsford Ltd. produced an algebraic edition.

At first, nothing seemed amiss. Page 188 of the April 1995 BCM, for example, gave a hearty, if brief, welcome to ‘this great classic’ and concluded ‘The best chess book ever written?’ Everybody was glad that new generations of players unreceptive to the descriptive notation could enjoy Fischer’s work, and nobody realized what Batsford had done to it.

Nobody, that is, until June 1996, when Fischer gave a searing press conference in Buenos Aires. He denounced the Batsford edition as forged and unauthorized and accused the company of having intentionally included many changes to it, in an attempt to make him look foolish. His salvos were reported in detail on pages 6-12 of issue 432 of the Spanish magazine Jaque (September 1996), whose front cover sported a photograph of Fischer holding up a copy of the offending book.

The magazine also reprinted a conversation some ten days later between Fischer and Juan S. Morgado in a Buenos Aires bookshop. Fischer declared that the Batsford team were ‘criminals’ and ‘conspirators’ and added: ‘They changed everything in my book, the notation, the format, the pages, the analysis … and without paying royalties.’

Batsford swiftly issued a statement, professing itself ‘appalled’ by Fischer’s remarks. It said that it had purchased the right to publish the book from Faber and Faber, and that this ‘included the power to make alterations to make the book suitable for the British market’. It was thus converted to the algebraic notation and, Batsford added, ‘our intention was to produce an edition that was accurate and faithful to the original. There was no addition or subtraction of intellectual material’.

John Nunn, the book’s typesetter, adopted a similar line of argument in an e-mail message to Larry Evans. It was quoted by the latter on page 8 of Inside Chess, 23 December 1996:

‘So far as I can see there have been no changes to the intellectual content of the book, either by subtraction or addition. Only one piece of analysis was changed, because a mate in four had been overlooked in the original book. Quite honestly, I can’t see any grounds at all for complaint.’

Batsford said in its statement that it had written to Fischer enquiring where royalty payments should be sent and asking whether he wished to be involved in the new edition. ‘The only reply took the form of a letter from Bobby Fischer’s lawyers, querying our right to publish the book. We can only presume that the response satisfied them, since they have not come back to us in the year and a half since then.’ Batsford concluded: ‘Thus we really don’t see any grounds for complaint, and continue to wait for Bobby Fischer to provide an address to which royalties should be sent.’

It would be pointless to speculate on these contractual details or letters, but the affirmation that the book’s content was not changed can be called, loud and clear, a falsehood. Fischer’s book had not only been changed, it had been butchered – deliberately, wantonly and more or less systematically.

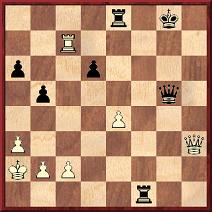

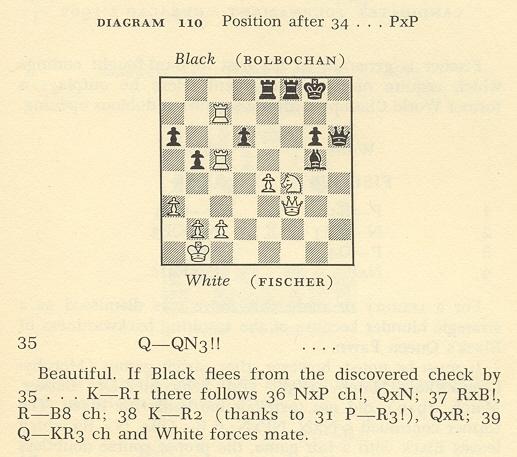

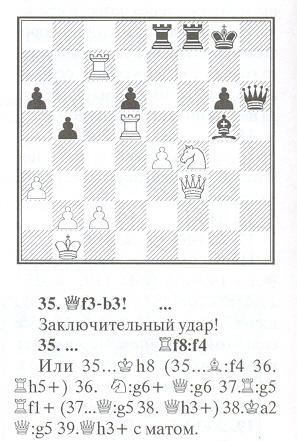

First, the case mentioned by Nunn to Evans, where the Batsford edition sought to correct some analysis in which Fischer had allegedly missed a mate in four. In fact, it was Batsford’s own blunder:

In this position, arising from a note at Black’s 35th move in Fischer v Bolbochán, Stockholm, 1962 (game 35), Fischer wrote that 40 Qxf1 leads to a win, but Batsford changed this to ‘40 Qh7+ Kf8 41 Qh8+ Qg8 42 Qh6+ Qg7 43 Qxg7 mate’. The only problem, of course, is that 42 Qh6+ is illegal, because 41…Qg8 has given check.

From page 135 of the Batsford edition

The November 1996 CHESS (pages 26-29) set out Fischer’s grievances (including the Bolbochán episode), whilst leaving in abeyance the question of how many changes Batsford had made. The January 1997 issue devoted nine pages to the controversy. First, there was a one-page account by John Nunn. He stated that he had been the book’s typesetter, not its editor, and objected to the claims by CHESS along the lines of ‘Nunn has added …’. He commented, ‘After such a time, it is impossible even for those who worked on the book to say exactly who changed what’. Nunn also said that there was only one change to Fischer’s analysis (i.e. in the Bolbochán game, now acknowledged not to be Fischer’s error after all). Next, Nunn disputed the claim by CHESS that Fischer had taken great care over his book. ‘If he was so careful, then it is hard to explain why there were over 200 notational errors and ambiguities in the original edition of Fischer’s book. In game 52, for example, there were seven such … It seems a poor reward to correct 200 errors and ambiguities but overlook one, and then be attacked for my involvement in the book.’

Most of Nunn’s other comments were in reply to CHESS’s criticism of the new book’s typesetting and presentation (i.e. double columns, the use of italics, etc.). These issues are not of direct relevance here, although they offer another example of the unfortunate desire to force Fischer’s masterpiece into the Batsford sausage machine.

Next up at the stand was Graham Burgess, then the ‘Managing Editor’ of Batsford’s chess list. He too stressed Batsford’s correction of ‘literally hundreds of errors and ambiguities in the original notation’ but added ‘nevertheless, it is indeed highly unfortunate that we introduced one error, the mate-in-four-which-isn’t in the notes to Fischer-Bolbochan, Stockholm 1962. This was the only change to the chess content of the book.’

Burgess gave a gaffe-by-gaffe account of how misunderstandings between Nunn and him had resulted in the illegal mate being published, and on the general question of textual changes he declared:

‘It is worth mentioning that it is standard in the typesetting process to make minor adjustments in the wording to improve the appearance of the text on the page in terms of spacing, line breaks, column breaks and page breaks.’

The reply by CHESS in the same issue addressed the above points head-on. The magazine admitted that when Fischer’s book had been issued the previous year it had given it merely ‘a quick glance’, on the assumption that ‘John Nunn, custodian of chess quality, had at least produced an accurate version of the 1969 original’. Concerning Nunn’s point that the original descriptive edition had many typographical errors (particularly in the moves), CHESS quoted Fischer’s acknowledgement that there had been ‘millions’ of typos, as well as his comment, ‘I don’t need them [i.e. Batsford] to correct anything for me, even with the help of computers. Of course the book has mistakes, but I can correct them myself. They changed my things on purpose …’ CHESS added that Fischer had taken great care with the book’s analysis.

The magazine then discussed the various statements by Nunn and Burgess as to who had done, or not done, what. For the record, it may simply be observed here that the copyright page of the Batsford book lists five people: a three-man ‘Editorial Panel’ (Mark Dvoretsky, John Nunn and Jon Speelman), a ‘General Adviser’ (Raymond Keene) and a ‘Managing Editor’ (Graham Burgess). In addition, Nunn is referred to as the book’s typesetter. He receives a further mention on the back cover: ‘Reset by John Nunn into modern algebraic notation, with many extra diagrams.’

As regards that typesetting, or resetting, CHESS noted that ‘Nunn had before him the task of neatly accommodating 384 generously laid out single column pages of the original book into 240 packed double column pages for the Batsford edition and ran into all sorts of problems. Rewording in order to shorten or lengthen text became the norm, diagrams frequently had to be placed out of sequence from related moves and text, losing impact, and, worst of all, in a few desperate cases, whole lines of text were actually eliminated. Sacrilege!’

Yet, as noted above, Burgess had claimed that nothing untoward or unusual had been done on the typesetting front. Jeremy Silman was later to comment acidly in his ‘Inside Chess Online’ review of My 60 Memorable Games:

‘Mr Burgess, I don’t know where you learned this “standard” typesetting law, but any major publishing house in the United States would instantly fire any typesetter doing this kind of thing. A typesetter who butchers an author’s work to make his own job easier should find a new vocation.

… Burgess seems to be saying that the typesetter is the one responsible for all the textual changes (and then he says that this is perfectly all right). Nunn says that he didn’t really make any errors, and that his only job was to typeset the book! Dr Nunn, are you responsible for all the textual changes? Is Burgess? Who is? Do you think that such changes are justified? Can you honestly say that you wouldn’t mind if I made hundreds of textual changes to one of your books someday?

Quite frankly, I am tired of Mr Burgess, Dr Nunn and Batsford pointing out the errors they corrected … while simultaneously excusing themselves for the mess they made of everything else. Why not take a mature stand and simply admit that bad judgment was used and, hopefully, that it won’t happen again? We are not dealing with a government conspiracy here, gentlemen. Isn’t it time to come clean and put this nonsense behind you?’

By that time, though, Batsford was disinclined to comment further, whether mendaciously or otherwise, and the shutters were put up. On many previous occasions the company had resorted to a similar policy of tactical silence, most notably on matters concerning the misconduct of Raymond Keene, where a hope-it-blows-over approach was the only chance.

Below are the front covers of various editions in our collection, as follows: the first printing of the original (1969) edition from Simon & Schuster, a subsequent paperback from the same company, two editions (still descriptive) from the British publisher Faber and Faber, and the 1995 Batsford version:

In the face of Fischer’s denunciation of Batsford and the latter’s refusal to admit wrong-doing, CHESS had engaged us to make an assessment of the extent of the textual changes made. It was apparent that a mere spot-check would not suffice, and we thus compared line-by-line the Faber and Faber edition and the new Batsford version. This verification work showed that over 570 changes had been made by Batsford, and a range of examples was presented on pages 45-48 of the January 1997 CHESS. We found that entire notes of Fischer’s had been omitted, individual words had been deleted, other words had been added and – the most frequent occurrence – Fischer’s wording had simply been changed without justification. Inconsistency had been introduced, a number of misspellings in the original had been left uncorrected, and many fresh mistakes had been added by Batsford.

In fact, the bad news started as early as the Contents page, Batsford’s carelessness being such that it reproduced the list of games from the original edition without changing the page numbers, which were thus all wrong. At the other end of the book, the headings for Fischer’s tournament and match results listings were incorrectly tabulated. In short, the care and attention accorded to Fischer’s magnum opus were no greater than what had been offered, over many years, to the seemingly endless stream of Batsford disposables which had inundated the chess book market.

With Fischer’s prose Batsford simply did whatever it wanted. Where Fischer had ‘Black’s better’, Batsford wrote ‘Black has secured an advantage’. Where Fischer said that a move was ‘murderous’, Batsford put ‘deadly’. Where Fischer used the term ‘accelerated Dragon’, Batsford preferred ‘the Hyper-Accelerated Dragon’. On page 48, Batsford altered the spelling of a player’s name – but wrongly, turning a Russian into a non-existent Yugoslav. After White’s 39th move in Game 60, Fischer wrote a 12-word note which Batsford just dropped. In Game 50, eight notes in a row contained modifications of the American’s writing. Another example of pointless chopping and changing is Game 52, and the note to Black’s 12th move in Fischer v Rossolimo, United States Championship, 1965-66. In the original edition Fischer wrote:

‘Better is the natural 12…Q-R4 (if 12…P-KN4; 13 Q-B6!, QxQ; 14 PxQ, P-N5; 15 N-K5, PxP; 16 PxP, NxP; 17 P-KR3 with a better ending); 13 QR-N1 (if 13 KR-N1, P-N3; 14 P-QR4, B-R3; 15 B-N5, QR-B1; 16 PxP, PxP; 17 BxN+, RxB; 18 R-N8+, R-B1 holds), P-N3; 14 PxP, QxBP; 15 N-Q4, NxN; 16 PxN, Q-R4+ with equality.’

Batsford took it upon itself to redraft the note as follows:

‘Instead, 12…g5 13 Qf6! Qxf6 14 exf6 g4 15 Ne5 cxd4 16 cxd4 Nxd4 17 h3 gives White a better ending, but the natural 12…Qa5 is better, e.g. 13 Rab1 (after 13 Rhb1 b6 14 a4 Ba6 15 Bb5 Rc8 16 dxc5 bxc5 17 Bxc6+ Rxc6 18 Rb8+ Rc8 Black holds) 13…b6 14 dxc5 Qxc5 15 Nd4 Nxd4 16 cxd4 Qa5+ with an equal position.’

Batsford was obviously making itself a laughing-stock. The Summer 1997 issue of Kingpin (page 68) carried a spoof Batsford advertisement featuring ‘My 60 Unforgettable Games’ (‘Fischer’s masterwork, totally rewritten but with no changes to the original text’). Also listed was the fictitious work ‘The Concise Batsford Book of Chess Quotations’, which included a Tarrasch observation: ‘Chess, in common with amorousness and musical compositions, has the ability to give contentment to people.’

It should not, however, be imagined that the revelations about Batsford’s behaviour provoked outrage in all quarters. In the letters section of the February 1997 CHESS, for example, Julian Hardinge of Glasgow was accorded about 70 lines to react to our verification of Fischer’s book. He spent most of his space attacking us personally, since he saw nothing wrong in what Batsford had done. ‘Examination reveals almost all of these differences to be entirely devoid of significance’, he wrote, without bothering to wonder why, in that case, Batsford had made the changes in the first place. Question: who is J. Hardinge? Answer: an associate of Raymond Keene, and the co-publisher of that appalling Keene/Divinsky book Warriors of the Mind. In fairness to CHESS, it should be added that in a subsequent issue it offered us an apology for having published such personal attacks.

Batsford found itself one other defender, though, again, it was hardly an impressive one. On page 41 of the January 1997 CHESS Graham Burgess wrote:

‘The comments of Larry Evans, in his Evans on Chess column from August 2, 1996, are worth quoting. Evans assisted Fischer in assembling the book, and wrote the introductions to the games. Having compared the two editions, he wrote of the Batsford book: “As Fischer’s collaborator on the original, I can attest that this edition is better!” Larry was also delighted to see some old typos corrected, e.g. 50…Kc7 instead of the faulty 50…B-R8 in Game 17.’

Indeed, on page 42 of the same issue of CHESS, Evans went further still, claiming that the above-mentioned change in Game 17 ‘goes a long way toward superseding all the other objections put together!’ Despite stiff opposition, that remark is perhaps the most foolish that Evans has ever made. Jeremy Silman later commented: ‘I was outraged when Larry Evans wrote that the correction of one obvious typo outweighed all the errors and changes.’ Even Hans Ree, who showed on page 95 of the 3/1999 New in Chess that he has yet to come to grips with the extent of the Evans problem, acknowledged that, at least in this case, ‘Larry Evans really played a silly role’.

It even turned out that, contrary to his earlier claim, Evans had not bothered to compare the descriptive and algebraic versions of Fischer’s book. His CHESS article had concluded, ‘The outrage over this edition seems like a tempest in a teapot’, and he used those last five words, followed by a question mark, as the title of an article published on page 8 of the 23 December 1996 issue of Inside Chess. There he claimed that Batsford had acquired the rights from Simon & Schuster (no, from Faber and Faber) and that the December 1996 CHESS had defended Fischer and found ‘some 600 changes’ (no, our article mentioned a total of around 570 and it was not published until the January 1997 issue). This caught Evans out. His own article had appeared before then, yet in it he gave the false impression that he had already seen the CHESS evidence regarding the extent to which Batsford had defiled the book.

In Inside Chess Evans concluded:

‘Yes, sloppy mistakes were made; yes, Bobby’s prose was disrespected; but I see nothing “malicious” in Nunn’s emendations, as Bobby claims. Since Batsford pledged to fix its next printing, the outrage over this one seems like a tempest in a teapot.’

On pages 3-4 of the 31 March 1997 Inside Chess we drew attention to an assortment of deficiencies in Evans’ position, but his replies showed him to be unrepentant and hopelessly out of his depth on what was, after all, an issue of principle, ethics and common sense. (Changing an author’s book without his permission is simply wrong.) Inside Chess decided to leave the matter there, on the grounds that our published exchanges with Evans had already ‘made him look a fool’.

As mentioned earlier, we counted over 570 textual changes, but in 1999 there was a curious twist to the story, with Fischer’s fury directed at us. In a radio interview on 10 March 1999 he called us a ‘bastard’ on the grounds that we had grossly underestimated the number of alterations made by Batsford; he asserted that there were ‘thousands upon thousands and thousands and thousands of changes’. In a subsequent radio interview (27 June 1999) he let fly again, even suggesting that we had given an artificially low total because we were ‘working for the Jews’. Since our figure was correct, in Chess Notes (items 2268 and 2298) we felt obliged to deal with Fischer’s substantive arguments, but in a sense this is a side issue. If Batsford had made a mere dozen textual changes to Fischer’s book, that would have been 12 too many.

Nor is there much point in spending time on Fischer’s dislike of our comment, adjudged far too weak, in the 31 March 1997 Inside Chess that he had been treated ‘scandalously’ by Batsford. Fischer argued in his radio interview on 27 June 1999 that it was far worse than that: it had been a criminal act. A similar view, as it happens, was expressed by Hans Ree on page 95 of the 3/1999 New in Chess:

‘In the Netherlands such changes constitute a criminal offense that could theoretically lead to a prison sentence. I hope the same goes for Britain. Anyway, Fischer had been quite right in his anger.’

The idea of anyone from Batsford being slammed into the cooler is implausible, whatever attractions it may hold for some. Messrs Nunn and Burgess left Batsford shortly after the exposé in CHESS, though they have remained in the chess book industry. An apology from them over the Fischer affair is still awaited. Evans, for his part, continues his deceptive attempts to play down what Batsford did, an additional instance being in the August 1999 Chess Life (page 13), where he merely says that the book was ‘not entirely faithful to the original’. (He also described it as ‘revised by John Nunn’.)

The corrected edition of My 60 Memorable Games ‘pledged’ by Batsford has never appeared, and it may be quite a wait for a proper algebraic edition, i.e. for Fischer’s own book without any arrogant attempts by others to improve it or fit it into a predetermined amount of space. It is hard to imagine that Fischer would ever become a Batsford author of his own free will, and the contractual situation for his book must be murkier than it was in the mid-1990s. But even if the rights to My 60 Memorable Games were on offer on the open market, where is the publishing house that Fischer could trust to bring out an algebraic edition with no changes other than those he himself wants to make?

The above article was first published in 1999, at the Chess Café. Three years later we received the following from a British correspondent, Steve Giddins, and quoted it in C.N 2762:

‘Regarding the embarrassment over the note to Black’s 35th move in Fischer-Bolbochán, Stockholm, 1962, where Batsford changed Fischer’s analysis to reflect a forced mate which in fact did not exist, it has now come to my attention that the same error is made in the Russian book 744 partii Bobbi Fischera. Like many Russian books, this one reproduces annotations from other sources (presumably without paying royalties), including those from My 60 Memorable Games. The relevant note to Fischer-Bolbochán (volume 1, page 283) ends “39 Qh3+ s matom” (i.e. “with mate”), rather than “39 Qh3+ Kg8 40 Qxf1 leads to a win”, as Fischer originally wrote.

It thus appears that the Russian authors have not only fallen into the same tactical trap as Graham Burgess did in the Batsford book but that they have also, like him, changed Fischer’s own analysis, rather than merely adding a footnote pointing out the alleged “error”.

The Russian book came out in 1993, two years before the revised Batsford edition, so the latter was clearly not the source for the translation.’

In C.N. 2768 we commented:

‘The relevant part of the Fischer-Bolbochán game in the Russian translation of Fischer’s own work, Moi 60 pamyatnykh partii, was identical to what appeared in the book 744 partii Bobbi Fischera.

As regards the volume by Fischer, therefore, the Russian translation (1972) and the Batsford book (1995) both made the same silent ‘correction’ of his analysis, i.e. they both introduced, in Fischer’s name, a mating line which was nothing of the kind. A plain question arises: was this coincidental?’

C.N. 3871 (5 August 2005):

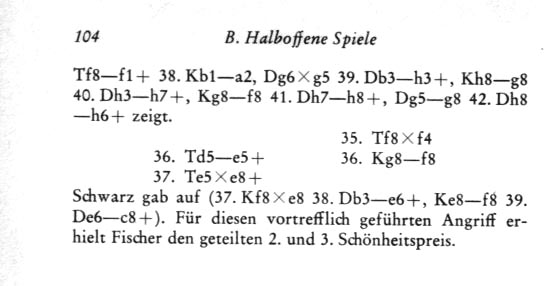

Zalmen Kornin (Curitiba, Brazil) points out to us that the same illegal line of play appeared in Schachmeisterpartien 1960-1965 by Rudolf Teschner, a book which was first published in 1966.

The imprint page of our copy has ‘© Philipp Reclam jun. Stuttgart 1966’ and ‘Printed in Germany 1972’, and below is the relevant extract, from pages 103-104:

English translation of the note at move 35: ‘Deadly, since 35...Kh8 would almost inevitably lead to mate, as is shown by 36 Nxg6! Qxg6 37 Rxg5! Rf1+ 38 Ka2 Qxg5 39 Qh3+ Kg8 40 Qh7+ Kf8 41 Qh8+ Qg8 42 Qh6+.’

This is the identical mate-that-isn’t line which Batsford misattributed to Fischer in 1995. It will be appreciated if a reader who has the first (1966) issue of Teschner’s book could confirm that its text is identical to what has been reproduced above from the 1972 printing. If such is the case, it will have been found that this spurious mate had appeared in chess literature even before the publication (in 1969) of the first edition of My 60 Memorable Games. [It was subsequently possible to establish that the 1966 edition of Teschner’s book did indeed have the identical text.]

C.N. 3876 (6 August 2005):

Below is a photograph of Julio Bolbochán, from page 55 of the February 1956 issue of the Argentinian magazine Ajedrez Revista Mensual:

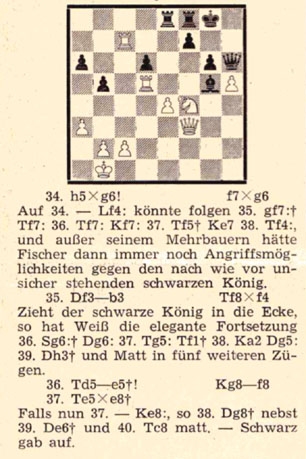

Peter

Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) has now found that the spurious mate

under discussion appeared in print shortly after the Fischer v

Bolbochán game was played. Our correspondent

quotes Ludwig Rellstab in Schach-Echo, 23 April 1962, page

121:

The relevant note is at move 35: ‘Zieht der schwarze König in die Ecke, so hat Weiß die elegante Fortsetzung 36 Sg6:+ Dg6: 37 Tg5: Tf1+ 38 Ka2 Dg5: 39 Dh3+ und Matt in fünf weiteren Zügen.’ (English translation: ‘If the black king goes into the corner White has the elegant continuation 36 Nxg6+ Qxg6 37 Rxg5 Rf1+ 38 Ka2 Qxg5 39 Qh3+ and mate in five more moves.’)

As the

Fischer v Bolbochán game was played in round 21 of the

Stockholm tournament, i.e. on 3 March 1962, we now learn that the

illegal

line was seen the following month already. Will this topic

produce any further surprises?

C.N. 4172 (15 February 2006):

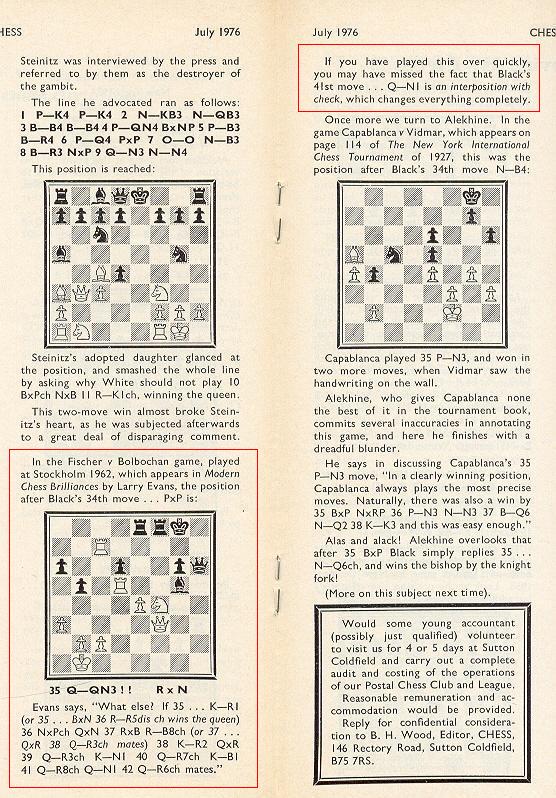

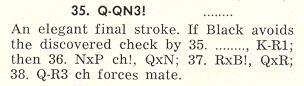

In a feature in CHESS, July 1976, pages 322-323 Irving Chernev discussed the Fischer v Bolbochán game and pointed out the non-existent mate:

The note remained the same in the 1994 (algebraic) edition of Modern Chess Brilliancies.

Addition (19 February 2007):

The following appeared on page 233 of Great Games by Chess Prodigies by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1967 and 1972), with a white rook at c5 instead of d5:

Addition (4 March 2007):

Leonard Barden annotated the game on page 78 of the April 1962 Chess Life. His note at move 35 gave a line in which Qh3+ did indeed force mate, since that was at move 38, not 39 (the Zwischenzug 37...Rf1+ being omitted).

Addition (30 March 2007):

The Russian translation of Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games has been reissued (Moscow, 2006), and in Fischer v Bolbochán the non-existent mate remains (page 128):

Other Fischer-related articles:

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.