Edward Winter

In his review of Kasparov’s Child of Change in the 8/1987 New in Chess, Tim Krabbé questioned whether Kasparov was wronged by the termination of his first match since he was trailing 3-5 against Karpov. This reasoning, originally voiced by hardly anyone except the American writer Hugh Myers, is now gaining ground. Two other critics of Kasparov’s latest autobiography who have echoed Krabbé’s doubts are Leonard Barden and Nigel Short. The former wrote on page xviii of the Financial Times of 21 November 1987:

‘Central to Kasparov’s thesis is the “day of shame” when Campomanes abandoned the 1984-85 world title match just after the youthful hero had recovered from 1-5 down to 3-5. Karpov still needed only one win to complete the six required for the match. Kasparov’s account of this episode repeats his earlier public statements and seems to have it both ways. In one paragraph he says, “I wanted no part in any deals behind closed doors”. In the next, “the FIDE proposal to stop now and start afresh ... wasn’t so bad for me ... to start play again at nil-nil was better than 5-3 against”. It is a strange plot which, by its victim’s own assessment, doubled his chances of victory.’

Under the title ‘Grandmaster of Self-Delusion’, Short asked on page 43 of The Spectator of 17 October 1987:

‘... what sort of conspiracy gives Kasparov a chance to start afresh the match, at 0-0, when he is 5-3 down against one of the greatest chess geniuses ever? Whereas, if the match was continued his chances of winning were, by his own admission, a mere 25-30%.’

There seems to be a distinct move away from how the termination decision was interpreted at the time; in 1985 it was widely condemned as Campomanes’ response to panic-stricken pleas that he save the title of his worn-out friend Karpov. That was the message in Kasparov’s fulminations against Campomanes, Karpov, Sevastianov, Gligorić, Kinzel, etc. in a series of press conferences and interviews. Journalists believed him and were unreceptive to other points of view.

Now, some three years after ‘The Day of Shame’, as Kasparov terms it, Child of Change provides an opportunity to analyse the affair more soberly. In investigating the reliability of the claims made by Kasparov and his supporters, we may reduce the issues to five basic questions.

1) Was Karpov exhausted towards the end of the match?

Karpov has always strongly denied it, so let us examine what Kasparov has said. On page 125 of Child of Change he claims that Karpov ‘had exhausted his strength’ and says on page 130 that ‘the blunt reason they called a halt was because Karpov was in no state to go on without the serious risk of defeat’. Unfortunately, on pages 124-125 he contradicts himself:

‘Some people – Karpov’s supporters, of course – have claimed that the quality of the chess at the end was very poor, showing that the champion must have been sick and that my victories were a fluke. This is not borne out by close analysis. Grandmasters have picked out the following games for “outstanding technical expertise, brilliant ideas or sheer sporting excitement”: numbers six, nine, twenty-seven, thirty-two, thirty-six and crucially – game forty-eight, the very last one. [In fact this anonymous quote is not by ‘grandmasters’ but by Raymond Keene, taken from page 140 of The Moscow Challenge.] The people around Karpov couldn’t understand what was happening. Because he had beaten me so easily in the early games, they assumed he must be unwell to be losing at the end. But Karpov himself knew better. He knew that in the last game, a good game of chess, I caught him out in one mistake. His people couldn’t see this. To them if Karpov is losing he must be sick, so we must protect him – and, incidentally, of course, ourselves.’

Kasparov reiterates this on page 143:

‘The people around him attributed my late victories to the fact that he was so exhausted, but Karpov knew better. He knew it was my chess that was beating him.’

2) Was Kasparov in good physical and mental shape at the end of the match?

Here is a quote from page 130 of Child of Change, referring to game 48:

‘Of course, it was very embarrassing for them that I won this game – and even more embarrassing that I won it with such good play. For this invalidated their argument that both of us were too exhausted to play good chess. As John Nunn has pointed out, forty-eight games is not at all an unusual number for grandmasters to play over a period of five months, and a number of the forty draws played in Moscow were short. I was certainly feeling in better shape than I had in September, as I kept pointing out to every official I came across.’

However, let us compare that with what Kasparov said in an interview in the 7/1985 New in Chess (page 7):

‘Exhaustion did exist anyway ... The most difficult to cope with was the psychological exhaustion, which increased even when a game was not so intense, because the match lasted a long time, and the responsibility was great. Regardless of whether a game was short or long, and even when one did not find oneself in extremely taxing circumstances, one could not relax, and had to think about the match all the time. One’s brain was working, and the nervous tension did not stop, not even for a moment.’

3) In what circumstances did Campomanes return to Moscow shortly before terminating the match?

In studying this question, Kasparov’s words on page 125 of his book should be borne in mind: ‘The final truth about this match, I believe, is as Grandmaster Keene reported it.’ Kasparov and Keene are close friends who have collaborated on literary and political projects; Keene’s writings are frequently quoted with approval in Child of Change.

Now, this is what Raymond Keene wrote on page 8 of The Spectator of 23 February 1985:

‘On the evening of Saturday 9th February, Campomanes was telephoned urgently from Moscow, with the stunning message from the world champion’s camp that Karpov, having lost two games in a row, was unable to continue and Campomanes should fly at once to Moscow to bail him out.’

It should, however, be noted that:

Raymond Keene himself (see May 1986 BCM, page 206) no longer defends his quoted words from The Spectator; nor has he retracted them.

Finally on this episode, one may note what Donald Schultz of the United States Chess Federation said on page 34 of the January 1988 Chess Life:

‘The recent campaign [Keene/Lucena v Campomanes] was one of the dirtiest I’ve ever seen. It was based on unproven innuendo. For example, the phone call that Campo received during the first Karpov-Kasparov match. They stated that it was from Karpov and that Campo was supposed to go to Moscow. I was there, in the room, when Campo received the call; it was from Svetozar Gligorić, and it asked that Campo go to Lucerne, to meet with Alfred Kinzel.’

4) Was Kasparov disadvantaged by the termination decision?

Firstly here, we may recall what Barden quoted: Kasparov’s words on page 133 of Child of Change about a new match starting at 0-0:

‘In a way this wasn’t so bad for me. I was sure I would win the second match. I had become much wiser than at the beginning of this one. And to start playing again at nil-nil was better than five-three against.’

Reviewing the book on page 37 of the Sunday Telegraph of 18 October 1987, Raymond Keene wrote:

‘Kasparov claims that Campomanes halted the first Kasparov-Karpov match “without result” just as the former was on the verge of victory.’

In fact, Kasparov stated (see page 141 of Child of Change) that his chances of winning the match were ‘about 25 or 30%’. It is not clear how Keene interprets 25 or 30% chances as meaning ‘on the verge of victory’.

[On pages 4-5 of the 4/1988 New in Chess Raymond Keene replied to our accusation of misrepresentation on this matter by simply writing, ‘I have a right to my own opinion’. That naturally disregards the fact that in the Sunday Telegraph he had been professing to report Kasparov’s claim – non-existent in reality – of being on the verge of victory. In any case, is it even Keene’s opinion? On page 51 of his 1990 book How to Beat Gary Kasparov he wrote that ‘at the end his [Kasparov’s] chances may have been superior’ (emphasis added).]

5) Was the termination decision defensible as a matter of principle?

Firstly, it should be recalled that nobody appears to have suggested outright termination of the match until Kasparov himself did so to Kinzel at the very beginning of February 1985. (Kasparov and Kinzel subsequently gave conflicting accounts of the circumstances and context in which Kasparov proposed that the match should be terminated.)

Kasparov nonetheless writes on page 155 of Child of Change:

‘... as Ray Keene pointed out when Campomanes visited London: “He proceeds from the arguable premise that a ‘decision’ was needed at all. In fact, no decision was necessary, since the match was proceeding according to regulations and these should have been allowed to run their course”. Precisely.’

The principle that ‘no decision was necessary’, which Raymond Keene expounded on page 42 of The Spectator of 4 May 1985 and repeated on page 20 of Manoeuvres in Moscow, is further illustrated by his words on page 204 of the May 1986 BCM:

‘... a vast amount of the criticism aroused by the K-K match termination is not because that termination damaged the specific rights or chances of either player. Rather it is because outside intervention from a third party violates the very nature of chess.’

(One notes in passing that the argument that Karpov had to be ‘bailed out’ has been dropped.)

However, on page 21 of Manoeuvres in Moscow Keene wrote:

‘Ironically, had Campomanes kept silent after game 48 and only stepped in to stop the match if there had been a further series of draws, his action would probably have met with widespread approval.’

So the argument now is that what was wrong was Campomanes’ timing, not the principle of termination (or ‘outside intervention from a third party’).

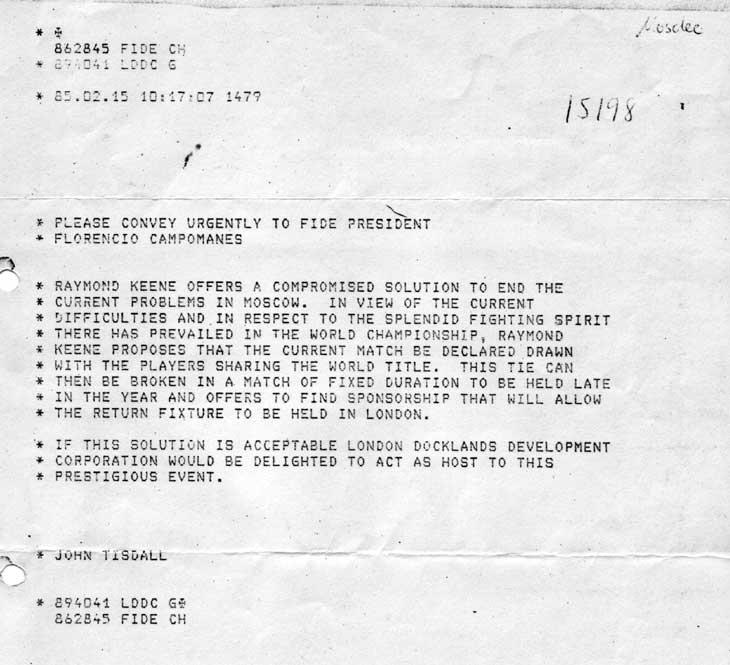

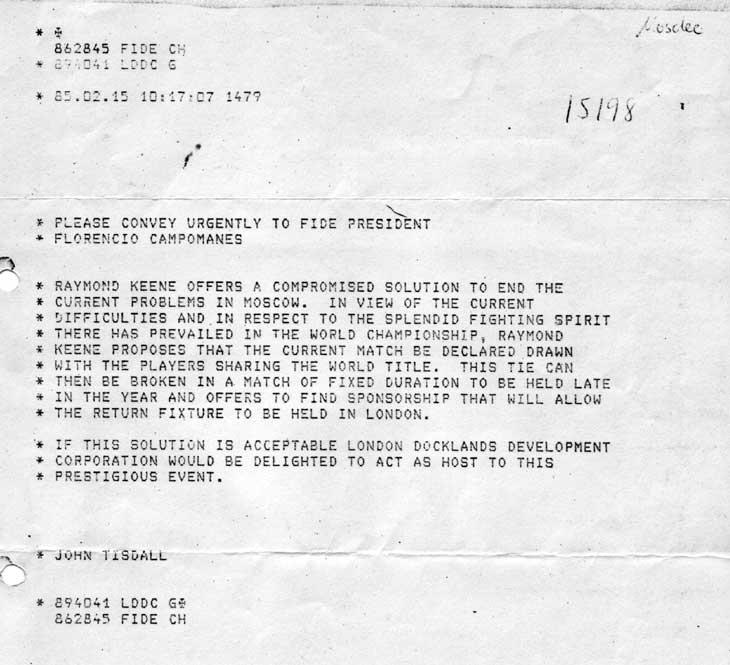

Raymond Keene’s protests about Campomanes’ decision need to be viewed in the context of the following telex, which was sent on 15 February 1985 from London to Lucerne and Moscow:

‘Please convey urgently to FIDE President Florencio Campomanes

Raymond Keene offers a compromised [sic] solution to end the current problems in Moscow. In view of the current difficulties and in respect to the splendid fighting spirit there has prevailed in the world championship, Raymond Keene proposes that the current match be declared drawn with the players sharing the world title. This tie can then be broken in a match of fixed duration to be held late in the year and offers [sic] to find sponsorship that will allow the return fixture to be held in London.

If this solution is acceptable London Docklands Development Corporation would be delighted to act as host to this prestigious event.

John Tisdall.’

Raymond Keene has provided two contradictory claims as to when the telex was despatched. On page 139 of The Moscow Challenge he indicated that it was sent after the final announcement by Campomanes that Karpov ‘accepted’ the termination decision and Kasparov ‘would abide by it’. However, on page 411 of the September 1986 BCM he stated that the telex was sent in the morning, in reaction to an (inaccurate) announcement on the radio that the match had already been terminated.

Conclusion:

It is only considerations of space that prevent further contradictions and inconsistencies from being given here. Let’s finish with one final puzzle, a brief quote from page 135 of Child of Change, where Kasparov describes the scene in Moscow immediately after – yes, after – Campomanes’ press conference announcement that the match was being terminated, with a new one to start at 0-0 the following September:

‘There was a great deal of shuffling and noise in the audience at this news. The video tape shows my trainers and myself talking and laughing among ourselves.’

The obvious question here is: why were Kasparov and his trainers laughing?

The above article was published on pages 53-56 of the 2/1988 New in Chess and was reproduced on pages 172-179 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, together with a further example discussed by us on page 392 of the 8/1986 issue of the Swedish magazine Schacknytt:

Another startling case of serial invention by a journalist writing about the Termination of the 1984-85 Karpov v Kasparov match is given in the present item. Firstly, let us examine the message which the President of the USSR Chess Federation sent to Campomanes shortly before the match was terminated:

‘To the President of FIDE, Mr F. Campomanes

Taking into account the unprecedented duration of the world title match between A. Karpov and G. Kasparov, which is still in progress after more than five months, and in which 48 games have already been played (that is two full matches under the old rules), the USSR Chess Federation, expressing concern about the health of the participants, requests a three-month suspension of the match.

As is known, there was envisaged in the agreement of the unlimited match Fischer-Karpov (1976 – sic) a break after four months’ play. This provision was included on the basis of advice of medical specialists. Yet the Karpov-Kasparov match, as already pointed out, has exceeded this length and is still in progress.

We also point out that the proposal to have a break does not run contrary to the FIDE Constitution, nor to the match regulations, and, we feel, would be met with satisfaction by the public opinion of the chess world.

Your positive decision would be helpful and in the interests of the development of chess creativity.

Respectfully yours, V.I. Sevastyanov

13 February 1985.’

Now, compare that with how B.H. Wood summarized the letter in the February 1985 CHESS (page 283):

‘… Vitaly Sevastianov, the ex-astronaut president of the Soviet Chess Federation, wrote Campomanes a letter on 14 February, again admitting that Anatoly could not go on and begging for a stop to the match, with Karpov retaining his title and Kasparov “permitted” a rematch later in the year.’

One may note that:

At the time of the Termination Affair the BCM (then owned by the British Chess Federation, of which Raymond Keene was an official) gave Keene a comfortable ride, and it was not until 1993 (page 228 of the May issue – an article by Murray Chandler and Bernard Cafferty) that an epiphany occurred, as the BCM belatedly (and euphemistically) referred to Keene’s practice of ‘reinterpreting history in The Times’. The following specifics were offered on that same page of the BCM:

‘Repeatedly attacking FIDE President Campomanes for halting the 1985 title match against Karpov “when Kasparov had won several games in a row”. Kasparov himself assessed his chances at only 30% at that point. The final score (5-3 to Karpov) was never mentioned, nor the fact that the re-match started with level scores.’

As noted on page 271 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, Keene also wrote, in The Times of 27 February 1993, that ‘Kasparov revived and began to win game after game’, and there was more of the same on page 49 of Man v Machine by R. Keene and B. Jacobs with T. Buzan (Brighton, 1996); that book asserted that the 1984-85 match was stopped ‘just as Kasparov had started to win a series of games’.

When there is such a premeditated and deliberate plan to deceive about, even, the basic score of the match, what chance exists of sorting out the complexities of the Termination itself? Back in 1985 (in C.N. 1020) John Nunn wrote to us:

‘... I doubt whether the full truth will ever be revealed. ... I have given up trying to reconcile the many conflicting statements about the events in Moscow. My own view is that it isn’t necessary to evoke any conspiracy theories; muddleheadedness, lack of communication and incompetence are enough to explain the whole bizarre story.’

But should chess writers and researchers throw up their hands and admit defeat? Is there really no longer any chance of determining the truth? In whose interests would it be for matters to be left unresolved? Below is a follow-up item we wrote in June 2004 (C.N. 3328).

The 20th anniversary of one of the most controversial happenings in chess history will come on 15 February 2005: the Termination of the first world championship match between Karpov and Kasparov. In C.N. 1990 (see CHESS, November 1993, page 50) we called it a topic ‘which chess literature (books and articles) has yet to settle authoritatively’, and it may be wondered whether any fresh details have emerged since then. Investigative journalism being virtually non-existent in the chess world, there is every reason for truth-seekers to fear (and for others to hope) that the 20th anniversary will come and go without new, accurate information being brought to light or old, inaccurate information being laid to rest.

Kasparov, for his part, has stated (on page 127 of his book Child of Change) that ‘the full story may never be known’, although he has often set forth what he calls his ‘theories’. And what about Karpov? His book Karpov on Karpov (New York, 1991) had the subtitle ‘Memoirs of a chess world champion’, but the Termination Affair was (remarkably and, indeed, shockingly) ignored. Are none of those involved in the controversy willing and able to state now, plainly and factually, what they do and do not know, so that chess historians are offered at least a sporting chance of piecing together the truth?

Our own attempts date back to 1985-86. On 1 January 1986 the then General Secretary of FIDE (the late Lim Kok Ann of Singapore, who was, in our experience, a gentleman of great integrity) informed us:

‘Mr Campomanes agrees to give you a written interview, an exclusive, though he has answered sundry questions on the Termination. Mr Campomanes is prepared to face any question you care to ask.’

As reported in C.N. 1098 [i.e. the March-April 1986 issue of our magazine], the planned interview did not work out:

‘Our questions (26 in number) may certainly have amounted to quite a grilling, but they were, if we may say so, fair and objective questions that Campomanes will surely be obliged to answer sooner or later somewhere or other.’

At one point we did receive from FIDE a Dictaphone cassette and transcript, but Campomanes’ answers (to only four questions) were so discursive and disjointed that turning them into a printable item was beyond our ability. We hope that, even now, an enterprising writer will be able to pull off the feat of obtaining from Campomanes his ‘definitive’ version of the events in Moscow. More generally, it would be most welcome to see a reliable journalistic write-up of the entire Termination Affair which is devoid of speculation. The matter is simply too important to be touched by the ‘I-think-I-read-somewhere’ and ‘My-guess-would-be’ brigade.

Sorting out fact from fiction is a time-consuming task, not least because certain ‘chess writers’ more pro-Kasparov than pro-truth have repeatedly warped the facts of the case; for innumerable examples see pages 221-225 and 269-270 of Chess Explorations and pages 172-179 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves. At least for now, it seems unnecessary to cite any such instances here, but we may do so later on.

In C.N. 1491 our own standpoint was summarized as follows:

‘On Termination Day, however, few knew that all these discussions [involving the officials and players] had been going on for over two weeks. In particular, hardly anyone was aware of the Kinzel-Kasparov negotiations. This prompted the widespread impression that Campomanes’ decision was “arbitrary”, and the FIDE President did little to help quell suspicions. Neither the question of whether Campomanes was right or wrong to stop the match (our own agnosticism has never been firmer) nor the repeated falsehoods written by his opponents in their press monopoly outlets can alter the fact that Termination Day in Moscow was a shambles for which Campomanes must take full blame.’

In conclusion for now, we add that our files include a personal letter from Lim Kok Ann dated 13 January 1986 which contains the following paragraph:

‘Campomanes states that at first (in December) only the suspension of K-K [1984-85] was considered, as a solution to the impasse – the players objected to change of playing hall “against regulations”; the organizing committee’s lease on the Hall of Columns had long lapsed, and the hall was required for funerals, inter alia (how do you like my use of the Latin?). Apparently Kasparov remarked that instead of a suspension he would prefer the match be terminated. This rash remark first put the idea to Campo that termination could be a solution, but “suspension” was as much against the regs as termination was, and suspension would have favoured Karpov very much. As for continuation, we should ask where and how.’

As matters stand, in 2005, is any consensus possible about the Termination, despite all the claims and counter-claims? We believe that few readers will disagree with the following summation:

The following comment by Yasser Seirawan at ChessBase in October 2006 is to be noted:

‘Campomanes, as we know, aborted the 1984/85 World Championship match. I make no judgment as to the rights and wrongs of that exceptionally complicated case; after all, it threw up so much contradictory evidence that the only fair-minded conclusion is agnosticism on whether or not Campomanes was correct to terminate the match.’

Addition on 11 January 2008. At Chessgames.com on 10 January 2008 Raymond Keene wrote the following (quoted here in full):

‘<sitzkrieg> you are in violation of the guidelines and your comments shd be taken down-however i cant resist pointing out a couple of things-

1 i have never knowingly purveyed any kind of falsehood in anything i have written

2 in the extract you quote winter seems to be unable to reconcile the facts that i sent off a telex message in the morning while elsewhere i refer to my message reaching moscow later that day-what he has forgotten -presumably because he does not get out and about much-is that moscow is three hours later in time than the uk, so it was perfectly possible to send a telex in uk morning time, while at the same time it was much later in the afternoon in moscow! that rather obviously explains why it was possible for me to know about events happening in moscow in their afternoon time while it was still morning time in london. this is so blazingly obvious i have never bothered to point it out before.

on top of that-in spite of winters desperate rearguard actions to defend the now defunct corrupt commie state- history has served its verdict on that disgraceful episode-if any umpire or arbiter in any other sport had halted the contest at the point campomanes did he wd have been lynched!’

Mr Keene mentions only one specific matter, and it is untrue. We have never overlooked the obvious existence of a three-hour time-difference between the United Kingdom and Moscow. Indeed, we drew attention to it in C.N. 1222 at the time the Keene/Tisdall telex came to light: ‘the identical text was also sent direct to Moscow, at 10:13:52 GMT (Moscow time minus three)’.

See also our review of Child of Change.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.